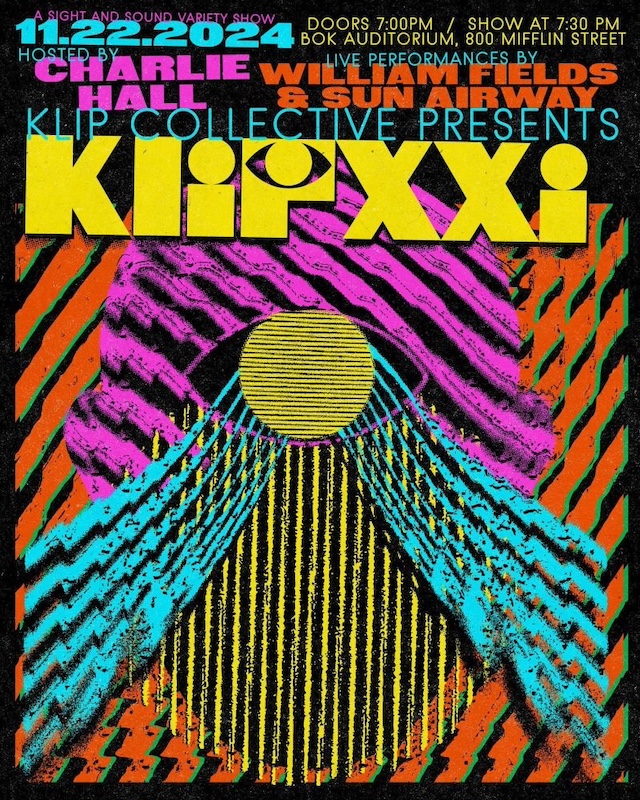

Hosted by Charlie Hall (the drummer of a little band called the War on Drugs) with transcendental live music and guests like Making Time’s David “Dave P” Pianka, projection mapping icon and party legend Klip Collective is celebrating their 21st birthday tonight at Bok in Philadelphia… and we’re invited.

Earlier this year, Canadian dance export Caribou transcended with Dave P. for Making Time on the rooftop of Bok Bar (on the roof at Bok Building, a former tech high school turned art space) for a free show I almost didn’t get into because it was “one up, one down” by the time I was at the front of the line. Spoiler alert, that thinned out the weak (Kidding!) and I got in and up.;*very The Get Up Kids voice* up on the roof, it was that signature Making Time metal slat top booth and pink rod lights and cool, happy, weird people including a boy holding a baguette.

You could see the whole city from up there and the sky at one point matched the lights and I was just so happy that I felt compelled to ask the person on the boards – who had glasses and dark, floppy hair – if I could take their picture for the ‘mems. He said, “Sure, I just do the lights,” and it hit me. “Oh my God, are you Klip Collective?” And they gestured like, ‘That’s me.’ I got my picture. So, that’s how I met Klip Collective.

Klip Collective is the force behind the storied light, sight, and sound experience Night Forms at New Jersey’s Grounds for Sculpture (arguably the Garden State’s most important, well-known, and, perhaps most importantly, accessible art museum), the Deck the Hall Light Show at Philadelphia’s City Hall, and now Time Loop at Crystal Bridges in Arkansas. Ricardo Rivera, the founder and mastermind behind Klip Collective, provides key visuals of the Making Time festival and event party series with Dave P, which has featured LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy, Four Tet, Avalon Emerson, and Jamie XX.

Rivera’s career as a visual artist and filmmaker predates Klip, which this Friday celebrates 21 years, with a foundation in documentary filmmaking, spans collaborations with Kurt Vile, Twin Shadow, and Simian Mobile Disco, and is a lighthouse for pioneering work in the innovation of projection mapping. (They earned a US patent on the technique when most of us just see pretty lights.) But what’s a concert or show without visuals? And what are visuals without music? For 21 years, Klip has made sure we don’t have to ask.

When I catch Ricardo Rivera over Meet, he’d just got off a long call for a project years in the making; can’t talk about it just yet, but it sounds big. Through the screen, a room with a bowling pin, a wall of posters, and desks of twisty wires, modules, and computers surrounds them. In this interview, Rivera teaches me a new word (“proscenium”), reflects on a whole US-drinking aged-person’s lifetime of work, and tells me a bit about tonight’s sight and sound variety show… and why we should meet weird with weird.

Klip’s your favorite artist’s favorite sight-and-sound artist. Check it out.

So 20 years was last year, and this is 21, because that’s how math works. How long does it take to put something like this together, for the pleasure of commemorating and reflecting on the work? Had you been dreaming – for when the time would come – that you’d want it at Bok? Have certain people there?

That’s actually a great question, because what we’re doing on Friday for the KLIPXXI celebration is something that’s a little different for us. It’s a little outside of our comfort zone, which is always good to do. I realize that. But our studio is in the Bok Building and I’ve been here since the beginning of this experiment that is now Bok. I’ve been doing stuff in the auditorium with them. Our studio’s here, sowe were talking about what to do to celebrate our 21-year thing.

Last year was just a mess, which is why 20 didn’t happen. We just didn’t have the time or energy. We just weren’t mentally there, whereas this year…I. t’s been a crazy year. We’ve done a lot of great work this year. I was like, “You know what? This year is actually worth celebrating,” and then we were like, “21’s a lot cooler.” Then we made this idea of “XXI,” which was even cooler. It looks cool, Roman numeral wise, and then we had a logo made, blah, blah, blah. Now we got merch! Developing this show for 21, I really just wanted to tell the story of Klip over the last 21 years because it has been quite an experiment. I can’t believe 21 years ago, in 2003, I was doing visuals at raves and collaborating with entities in the city like The Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, but I was projection mapping, and I had this whole idea of creating projection mapping as a business when no one had ever even heard of it. It was kind of a different time and almost a different place, so how do we celebrate 21 years of Klip? I didn’t want to do a chronological storytelling thing – that was the last thing anyone wanted, that just sounds boring. The thing is, though, is I’ve done a lot of speaking engagements over the years. It’s a thing I would do as a side hustle. There are all these little bits and pieces from my presentations, so I was like, “Why don’t we just, in a non chronological way, tell some of my favorite stories and talk about the collaborations,” which I like to see as the “collective” part of “Klip.” It’s not a traditional arts collective. I just called it Klip Collective just because I like the pun of the words. The idea of collecting clips to project onto things, and that was kind of the dumb idea behind why we’re called Klip, but I did want to talk about the collaborations because that’s really what I love about what we do so much.

Michelle [Barbieri], who runs Klip with me and is also my life partner, has been there the whole time. We’re like a typical married couple. We bicker and talk about things; she sits across from me usually in the studio here. She also hates when I put characterizations on her… I’m failing left and right here. I can feel her yelling at me in my head [Laughs], but she was like, “I don’t want this to be the Ricardo show!” I’m like, “It’s not really, but everyone kind of wants the Ricardo show because they want to hear my stories, everyone I’m talking about,” so that’s kind of what it is.

Whenever people visit me in my studio, we always end up sitting here at my desk and I end up telling crazy stories about things that happened on this gig or that gig. Like real storytelling, it meanders and one story leads to another and I’m always bringing stuff up on my computer and showing people things that they haven’t seen before, so that’s what I wanted to do. Basically, on Friday, it’s literally going to be that. I’m using my good friend Charlie Hall, who is a drummer for the War on Drugs and who used to be across the hall from us here. He would always just wander in over here and we’d hang out and he was kind of that person a lot. He’s kind of like my foil in that sense. So, I’m literally just setting up a desk on stage at the auditorium with a 30 foot wide projection screen. I’m also projection mapping the proscenium, and Charlie and I are going to have a conversation and I’m going to show things.

I think one of the first things I show is a video I recorded 21 years ago, and it’s funny because it’s before cell phones, and it’s, like, me. I’m literally talking at a video camera, which is now absurd when you think about it. It’s very disarming because I’m much younger and I sound like a complete idiot at times, but it’s fine. Then I’m also showing a film I never finished that I made over 20 years ago that I directed. (My friend Dom shot it.) I had an intern once here at Klip and he found that footage and he just started throwing it together and I was like, “Oh my God, this is actually kind of cool.” And they’re like, “Why didn’t you edit this?” I was like, “I never finished it. I wanted to do all this other stuff and I never finished quote unquote shooting it,” so it’s a weird documentary about a farmers market in the middle of Delaware that I used to go to that’s super weird and super funny and cool, so I’m showing that.

I’m bringing on old collaborators like Bill Fields, who is an electronic music producer. My friend Jon Barthmus, who had a band called Sun Airway; I did all their tour visuals and did bunch of music videos for them, and Jon actually eventually started doing original music and scores for my other work. There’s a cool story there where the street went both ways. Music is such a big part of what I do. Of course, I’m going to bring Dave on stage. I’m going to have a stupid Making Time story I’m going to tell. It’s just an hour-and-a-half to two hours of us just kind of… Well, hopefully it’s conversational, almost like we’re shooting the shit, and then it ends with a big montage of our work, and we’re making mega credits. […] It’s basically a credits scroll of everyone that has worked for Klip, and I think it’s seven pages long. It’s like, everybody, but it’s cute. It’s like senior superlatives, and a lot of key players get funny, cute credits. Yeah, it’s like a celebration of 21 years of doing this silly stuff that we do. It’s kind of weird, that that’s all I’ve been doing for 21 years. It’s kind of nuts.

Would you say that Klip Collective could be applied to that you’ve been collecting folks that are now kind of like a production family? Like everyone in your credits is kind of part of the Collective in a small or big way?

Yeah, absolutely. People come and go and that’s a real family. One of the credits is an intern who left us to work at Facebook. It’s just like… that’s what happened and that’s ok! There are people that were interns and then ended up working for me properly, and then they went on and they’re doing amazing things, in other cities, in this vein, and it’s great. I love that, and I love that it’s kind of familial in that sense. Then there are people that are still here. There are people that have left and come back.

I remember I used to do a bunch of stuff at Sundance and I remember one time being at a workshop and the whole thing was: “Hire people smarter than you,” and I really took that to heart. Doing the stuff that we do, especially when you look at the larger multi-installation pieces, the big projects that we do, it’s just a bunch of awesome people I’ve been working with for a long time, but they’re all really good at what they do. It’s cool because I’ve been doing this for a while and I can do a lot of this stuff, and there are things that I do… I actually now got to the point where I purposely do things myself, by myself, so that my hands can still get dirty. I can still put my hands on things. Passages [the exhibit at St. Michael’s Church in Philly] is a great example of that. I just go and just do Passages myself and it’s really cool. But these bigger projects, I have all these people.

I have a guy, Florian [Mosleh], who is the smartest guy in the room and he is a projection mapping rockstar. He’s designed core visuals for Drake and shit like that, so he’s a big deal, but we’re really good friends and we’ve been friends for a long time and we’ve been working together a long time – he loves working on my projects. They’re collaborative and it’s like a big family. I love when the band gets back together. All these different people that do really intensely good specific jobs.It’s like a heist. It’s a lot like Ocean’s 11. I’m Frank Ocean. I’m the one that has the big idea, but I need a guy that can crawl inside a box this [Gestures] big, I need a guy that’s really good at bombs, and I need a guy that can steal things.

I have all these weird specialist people: projection mappers, animators, production designers, projectionists, musicians, composers, technologists… all these people kind of combine and we work together to make these big projects. And we do it, and we’ve made a whole freaking career out of just doing this weird thing that I kind of made up. It’s pretty cool. I always just want to keep doing it.

I remember during the pandemic – I always tell this story – I had this one project. I had done this thing called Nightscape at Longwood Gardens eight years ago or something and it was really successful and it was really cool. I had all these projections and light installations throughout Longwood. I remember that Steve Wilson and Laura Lee Brown, who are these massively wealthy art collectors that I met through Creative Capital, came to see the exhibit. Of cours, I walked them through it, and I’m like giving them a personal tour of the exhibit and they fell in love with it and Steve Wilson was like, “What happens when the show’s done?” I was like, “I don’t know!” He’s like, “Can I buy the equipment and you do something for me?” I was like, “Sure!” That’s what he did. He ended up buying all the equipment. It sat in a barn for years as he developed this space. He had this horse farm out of Louisville, Kentucky, and I worked with this architect and we made this path by this creek. He had this barn that he turned into this really beautiful bar/restaurant, so you go and eat and then you go down this trail and there’s this boardwalk that’s by this creek in the woods. I took all the Longwood gear and I did all these installations in that space just for that, but it was this weird project. It took forever. And to put it this way: when I was flying to Louisville for this project during the pandemic, it was me and three other people on the plane, to kind of paint a picture of that time. It was just past Windexing your groceries, if that makes any sense in the timeline of pandemic. It was a weird time and I didn’t know what was going on, but I remember my team being there. We’re working outside and it’s three in the morning. We’re sitting on this beautiful wooden boardwalk that’s in the woods and my projectors are on and I’m mapping these trees with my team and I’m like, “This is my happy place.” I’m in nature. I had my projectors and my computers and all my nerd friends doing my weird art with me and I just started, like, sobbing. They were like, “What’s wrong?” And I’m like, “I love this so much, and I’m so scared that we’re not going to be able to do this anymore,” because I didn’t know what was going to happen.

I really believe in this… I really love that moment, though, because I do appreciate so much of what we’re allowed to do here at Klip, and the projects that we get to do. I don’t know if “privilege” is the right word, because I worked really hard to get here [Laughs], but it is a privilege to me and I don’t take it for granted. I really love every opportunity we get to create these amazing experiences for people, and it’s great to be able to do this and to develop it further, to make it better.

There’s other people doing what we do now, which is crazy. And it’s like, “Ok, I see you! I’m going to make it fucking cooler now. I’m going to make it better.” Having that opportunity, it’s really cool. It’s exciting. I really enjoy it. It’s a whole thing.

When it it comes to working with a large group of people for scaled projects versus by yourself (you’ve been very busy this season, I want to note that), how much efficiency or creativity do you sacrifice – or gain – working by yourself versus a bigger group? I’m sure it’s like a sliding scale of positives and negatives of working lean or bigger, but then there’s an opportunity to scale and spread yourself a little thinner. So, very open-ended question, but what’s your perspective on that?

Yes, 100%.I think it’s a great question and it’s something that I think about a lot, because the word “artist” gets thrown out a lot and I always get a little weird. I don’t call myself an artist. You can call me an artist, that’s fine, that’s great. I love when people call me an artist. It’s like, “Please, cool, thanks.” It’s like, you don’t call yourself a genius, but someone can call you a genius and you’re like, “Thanks.” That gets thrown out a lot and I get a little wishy-washy because the idea of an artist is like, you know, they’re painting… it’s like a singular human expression. I always think about movies, and the idea of ‘auteur’ and the idea of the auteur theory. I went to school for film studies. I studied film studies when I was at college, and I remember reading about the auteur theory and I was like, “I love this.” It’s a Hitchcock film because A, B, C, and D, all because he had a look and he had a vibe. But being a filmmaker is a weird job, and I kind of consider myself more of a filmmaker than an artist. If I had to pick, I’d probably consider myself more of a filmmaker because I’m trying to create an experience. Not tell a literal narrative story in a traditional sense, but I like working with lots of people and the construct, and when I’m in that role, I’m able to do things I can’t do by myself.

One of the things I love about these bigger experiences that we create is that they’re multiple installations that people get to go through and I’m able to create an experience, a feeling, a vibe as a sum of those parts. That’s very exciting and I would never be able to do it by myself. I’m able to work with different people on these different pieces because they’re different things. Some are just light sculptures with sound. Some have projection mapping and heavy 3D animation, which I don’t do. I’m able to work with these people and form a thing that we all get to create together, but’s in my mind. It’s still in my mind. I see it first in my mind’s eye before that process becomes is a whole thing.

That kind of goes back to music. A lot of time I develop the music with my music director Julian Grefe, and we’ll make the music for the thing that’s a vibe. We’re talking about it like, “Oh, it’s going to be this space, and everything’s different,” and we talk about it and then he makes the track and I work with him back-and-forth on the track. Then I take the track, and then I work with different animators sometimes, and we listen to the song and I’m like, “I wanted to do this and do that.” In that sense, I’m able to very specifically create something that I see in my head and execute for people to literally… When you walk through, Nightscape [at Longwood] or Night Forms that I did at a Grounds for Sculpture, I saw that whole show in my head. You’re walking through my imagination. That was a great representation of something like that; I walk through the space and see what I want to do. We create it and there are changes and things, but at the end of the day it’s very, very clear what we’re doing and how we’re doing it.

When I’m working alone, when I do Passages, it is a pure experience for me as a video performance artist. I am improvising the entire time up there to whatever is being played. I create new things every month because now people come and they bring pillows and blankets and they lay down and they stare at my projection walls for three to four hours, and I’m like, “Holy shit, these people are paying attention to what I’m doing.” I kind of take that into account, so every month I’m like, “Shit, I’ve got to make new stuff. I don’t want to keep playing the same thing over and over.” Plus, I want to adapt to the different musicians that are coming, but it’s a pretty pure experience for me. The mapping – I map it myself. I’m improvising, but I’m using a lot of work… I mean, I go to the well. There are things that I projected at Passages that I made 20 years ago that I’m remixing and re-contextualizing, or I’ll use an animation that I collaborated with somebody on 15 years ago. I know those animators always see me projecting stuff and they’re like, “Mhm, I made that.” I’m like, “Yeah, but I paid you to make it and you made it because I told you how to make it, so it’s mine.” So, it’s a weird thing of ownership and that’s why the artist thing is a weird weird term for me. As far as, “Who’s making this? Who has ownership of this? Why is it here?” It’s like… I try not to think about it too much. I just like making these beautiful things for people to enjoy. And, how we get there, who knows?

I think there’s a lot of work of yours that people enjoy that they may not attribute to Klip Collective but they’ll attribute it to The City. Like, the Deck the Hall Light Show [at City Hall], for example, or the Grounds for Sculpture show, which can be attributed to New Jersey.

It’s weird. I mean, the City Hall thing – everyone was like, “Why don’t you put your name all over this?” I’m like, “I don’t want to put my name up there. I think it’s tacky,” and, honestly, the light show was a gift to Philadelphia as far as I was concerned. We got paid to do it. but it wasn’t ‘The Klip Show.’ It was like, “Merry Christmas, fucking Philadelphia. Here you go!” That’s really how I felt, which is cool, but everyone was like, “Why don’t you guys… no one knows it’s you!” I’m like, “Does anyone care?” Honestly, it’s a weird thing. What we do sometimes is thankless, but at the same time, I know people appreciate it. It’s also a weird thing because I’m 49. I grew up in a time when just saying your name… I always remember rappers would be saying their name over and over. I don’t know, but I always thought it was kind of weird. It’s just not my thing. I’d rather just… I think it’s cooler for people to find out later who made it than [Announcer voice] , “KLIP COLLECTIVE PRESENTS!” I’m not going to do that, fuck that. Although, Friday it’s going to be all about that [Laughs].

That is interesting, though, because it is kind of a part of a roster. You’ll have a poster and it’s Klip Collective and whoever you are collaborating with. That is important because it also allows for the work to continue in a way, so I’m sure it’s a little bit of a balance with that. Now, you were talking about how you were working during the pandemic in Kentucky. I’d love to know kind of where the development of the Grounds for Sculpture show came on that timeline, because it was one of the first big things in the area that brought people together outside. I remember shivering in gloves around my cups, but that was really special. It was an opportunity for people to be together and enjoy art and music together during the pandemic. So, I’d love to hear a little bit more about that.

The idea of doing an exhibit there actually happened before the pandemic. They came to us! We went up there, I looked at the space, and I was like, “Holy shit, I have a million ideas. Let’s do this!” And then the pandemic happened and we were like, “I guess we’re not doing anything!” It was right in the middle of us doing the Kentucky thing when they hit us up again and they were like, “Hey, we want to continue exploring this kind of idea.” We were like, “Let’s get people together outside!” Because it was like this whole thing, like, “We’re outside! We can get people together to enjoy art again,” so we started that process.

It’s funny, I talk a lot about the pandemic and I’m going to talk about it on Friday again, and I know everyone’s tired of talking about it, but it was a weird time, right?

It wasn’t that long ago! It’s still affecting people.

I know… my brain just was like, “Trump’s president… you know how that ended last time,” but I have to say – and it was terrible, people died – but it was a strangely opportunistic time for me in a way that everything stopped and it forced me to stop and slow down and think about things. Then when Grounds for Sculpture came back to us during the pandemic to say, “Let’s keep this moving,” I had the headspace that I really needed to put that show together. And when I say this, I mean it in the most honest way. In the past when I did Nightscapes at Longwood Gardens and Electric Desert at Desert Botanical Garden [in Phoenix, Arizona] and even the thing I did in Kentucky, they were cool. I was figuring things out and having multiple installations, but I felt like Grounds for Sculpture was the first one where I really dialed in on creating a larger whole, made up of the sum of its parts, with all the pieces. I really had a vision for what that show was and what I was trying to get at – which was very dystopian, by the way. It was very like, “Oh, shit, we’re living in this dystopia. Why can’t it look like what’s in my head? Or more like Bladeunner, or whatever?”

I was like, “The cyberpunk dystopia looked way cooler in my head.” We were experiencing a real cyberpunk dystopia with a pandemic and this crazy president and all this weird shit happening, and I felt like I wanted to create that world, but not the bad part of it – the cool looking part of it. How I saw that… this kind of technological future, but making art within it, and that’s why there’s glitches everywhere and these weird little things happening. There are moments, there are bugs. Everyone’s like, “What’s with the bugs?” and I’m like “Things don’t always work right and I can’t explain it so sometimes there’s some bugs in your shit.”

Plus, bugs survive through any circumstance, so they’re our heroes.

But it was a really great project to work on because I had the head space to really explore the hyperreal, if you will. That’s really what I was trying to get at and be able to ask questions and try different things that I wouldn’t have before, so that was really a great project for us. I really, really enjoyed putting that show together because we just had a lot of fun making it. It changed me, and now I’m making sculptures!

Like our exhibit [Time Loop: A Forest Light Experience] at Crystal Bridges [Museum of American Art] in Arkansas right now – it’s up till January. We made three sculptures; these are the 3D printed versions of them [Shows three little sculptures]. I started working with the atelier and we designed these objects and then they made them seven feet tall, and they’re made for projection mapping. They’re really cool.That’s what we’re currently working on, but without Grounds for Sculpture, I don’t think I would have gone down this path of making my own video sculptures.

So, no Night Forms at Grounds this year?

One day we’ll come back, but yeah, we’ve moved. They were like, “Let’s just do three years,” and we’re like, “Ok, that’s fine.” But maybe we’ll come back! The future is wide open. Who knows? A lot of people from Grounds for Sculpture came to our opening in Arkansas at Crystal Bridges. I know they’re like, “Where is this going after?” And I’m like, “Maybe your place. I don’t know,” so we’ll see. It’s open for discussion. I’d love to go back, but I also felt like we needed a break, as well.

New environment and then now the opportunity to create the sculptures! Very jealous of them, though. I have never been to Arkansas.

You should go. Bentonville is actually pretty cool…Time Loop has five sculpture, one light installation… but one light installation is like a gazillion – hundreds of lighting fixtures – and there’s three large projections and sound. It’s a 500 foot wide forest… it’s crazy. That piece is crazy.

So does the exhibition space or curator own the equipment and the sculptures that you create? For example, with the three exhibits that you did at Grounds, is it the same equipment every time? Just wondering how that works!

It’s very gray. For example, at Grounds for Sculpture, they ended up purchasing equipment from another exhibit that I had that was like “Do you want this?” And they’re like, “We’ll take it.” It made my exhibit better. We usually dictate what we need and it’s usually within a budget. “We have this much money. This is how many installations we can do.” Do they own it? Usually they own it. Sometimes they don’t, but things are changing.

At Crystal Bridges, they already owned a ton of stuff. They had a ton of projectors. I’m the third one to exhibit in this space, so they had a ton of lighting equipment and sound equipment and projectors, but then I also brought my own, and they’re actually renting some equipment that I brought for the time being. These sculptures are owned by me, by Klip. So when the exhibit’s done, we have them. Where they’re going… I don’t know. That’s a really good question. I’m terrified, because I live in a South Philly row home. It’s like, “I can’t put them there, no.” We’ll find a place for them.

Do you do storage units?

I could put them in storage, but I’m hoping to like…

…put them in the next spot?

I want to put them in something. That’s the thing – I like doing site specific work, but at the same time, I’m trying to create things that can travel, because then it’s like I’m doing less work, but it’s continuing. I’m pretty sure they’ll tour, though.

I’m sensing a theme of recycling and repurposing clips as well as trying to find concurrent logistics for the sculptures… and some of the same people and also some similar ideas, but turned into something new every time. Speaking of the pandemic again, to segue into your partnership with Making Time, were you part of the Moshulu event on the boat? What was it like to electrify the boat? I remember Avalon Emerson posted a picture and the caption was “Philly ain’t easing into it.”

That’s funny. How do I say this? I’ll probably never do a show in the Moshulu again, but I had fun there and it was really great transforming the space. Before that, during the pandemic, Dave and I did this Making Time hologram festival of DJs [officially called the MTXX: A Making Time 20th Anniversary TRANSCENDENTAL Social Distancing™ Celebration; one dollar from each ticket sold went to PLSE and the Plus 1 for Black Lives Fund] , and it was just me and Dave here. I would get all these DJs sending me sets and I would set up a light installation. I would make a hologram of them playing and I would do the lights and visuals live during their sets. I did, like, so many of them. They were super cool.

But I kept saying when Dave and I were talking, and we always talk about this, how I equate art-making a lot with sports, because I’m from Philadelphia and Philadelphia is a sports town, and you got to be into sports. This is who I am. I’ve been an Eagles fan my whole life. I equate a lot of things with sports, so I’m like, “This is practice.” We talk about practice, like Allen Iverson’s quote talking about practice and I think it’s really important to practice. I remember we were doing all these things with the holograms and Dave and I are working together doing this virtual music festival. I’m back there cranking out set after set, doing live sets of lights and stuff, and we were both like, “Man, we’re so ready. We’re so tight right now. We’re so tuned up; we’ve been practicing!” So as soon as we were able to do a show out of the pandemic, I was like, “Fuck, let’s go. I am ready,” and we just fucking smashed it. It was super fun. It felt so good to have people dancing again and to be able to do my thing with the lights. There’s nothing like it. Some of the things that we do, like doing something for Grounds for Sculpture, is very prescribed. It’s very thought out, I spend months putting it together and thinking about it. Even Passages, it’s very cerebral and I’m in there, but I’m still kind of got my hands on it. Making Time is pure muscle for me. It is pure muscle memory for me. It’s like we get together – Dave and I have been working together for 20 years – and we go into a space and I’m like, “Let’s do this, this, and this.” He’s like, “Yeah, yes, let’s do this.” And I’m like, “All right, awesome.” So I come up with how I’m going to light up the space, and then we set it up and then the music comes on and then I’m back there and I’m just like, “Let’s go.” It’s just weird. I become trance-like. Everyone’s like, “How do you know what’s going to happen?”And I’m like, “I don’t!” I just know music. It’s like playing an instrument. I just know when the breaks are going to happen. I’m just feeling it and I’m having fun and that is very exhilarating for me. And it’s also, like I said, practice. It’s like playing a musical instrument. You have to practice.

I have all my tools – different tools that I make and create that I use to do these things. We’re now making our own lighting controllers [pulls out lightning controller]. This is a lighting controller we made here at Klip that’s specially made for the way I do lights in the stupid way I do lights. It’s nuts. You’ll see something cool when I plug it in. I have this guy, Coulter, that works for me. He is, as Mario would say, an addition of one. All right, I’m plugging it in. [A piece lights up with a neon logo – Klip – it makes a little owl or hooting sound sounding like one of the songs from the Frog Head Rainbow installation from Grounds.] It’s pretty cool, but yeah, it’s a weird MIDI controller for my lights and it works really well. I took it out for a ride for the first time during the Making Time Festival this year, and it was awesome.

About practicing, there’s this quote, I haven’t been able to attribute it… something like how the mark of an expert isn’t how one avoids mistakes, how one recovers from them, and how quickly. The ability to change plans and pivot if things go off script, is a bit of the practice I think you are referring to.

It is. That’s called being fucking professional. When people can’t do that, I’m like, “What the fuck are you doing here? Come on. We’re pros here, let’s go.”

I make tools that are made to make and enable that process and make it better all the time. It’s so funny – we just had a Passages this last weekend and we were joking around and afterwards. I was like, “Man, I scored a hundred this week.” I didn’t make one… like, every performance, I’ll hit a clip, change a video clip while it’s all the way up, for example, and it just switches and I’m like, “Fuck!” It’s a mistake, but no one ever notices. What’s so funny is at Passages, everyone is so quiet and respectful there. It’s like you could hear a pin drop sometimes, because it’s like ambient electronic. I’ll do that and you’ll hear me in the booth go, “Fuck,” and everyone would look at me and I’m like, “Sorry.”

And we’re in church.

Like no one would even know you fucked up if you didn’t say something, but whatever. I did score 100 this weekend. It was all very clean transitions. It’s been nice. I upgraded the situation; I bought back some of the equipment from Grounds for Sculpture, some of the projectors that I had there, and I’ve donated them to the Passages space for the season. They’re in there and they got an upgrade. It looks great. It’s way more immersive, looks better. It’s crispier. Everyone’s like, “The projections look so crispy.” I’m like, “Yeah. Lasers, man. Sick.” They’re laser projectors. That was a big technological jump in projector technology over the last few years, is that they started making projectors that utilize a laser engine as opposed to a xenon lamp. The laser projectors – the colors are way brighter, way more brilliant. The image is crispier and they last longer, which is really nice. That’s good, too, and it’s better for the environment.

Technology! And you’re investing in a city institution.

Like I said, I give back to this town as much as I can. I love it here. If you hang out with me long enough and you talk about Philadelphia, I’ll talk about how much I love it here. Go Birds! And I’ll always say this: It’s a great place to make art, but it’s not always the best place to show it. I’m constantly trying to fix that second part. I make all my money outside of Philadelphia. Klip cannot succeed in the way of doing what it does without doing it in other places, unfortunately, but It’s a great place to be, it’s a great place to make things. It’s a great place to collaborate with people. It’s a great place to fail, which is really important as failure is a very good thing in the creative process. You need to create a space for you to try things, and sometimes those things don’t work and that’s ok. It’s ok. Rocky [Balboa] didn’t win the first film. He didn’t win in the first film. He didn’t win, and that’s okay.

That definitely speaks to the city. I’ve known of artists, makers of kinds, who love making their art here. Do you have an opinion on why you make money in places other than Philly?

Budgets. Certain places have bigger art budgets. It’s weird and I don’t know, but it’s something I can’t really explain as far as geopolitical economics. I mean, Philadelphia does have a vibrant art scene and there are things here. Like what we did at Longwood Gardens was very close to Philadelphia, and we did City Hall for years, but it’s just hard. I don’t know. Philadelphia is a very fickle, fickle city. We’re a tough crowd. I mean, arts funding in general is completely shit in the United States to begin with, and it’s only going to get worse in the next four years, I can’t even imagine… I don’t want to get into it too much because I don’t want to trash other institutions, but Philly has a tendency to get in its own way, I think, sometimes.

Dave and I do a lot for this city and I don’t think the city cares, to be honest with you. Not the people, but the city – they don’t give a shit. We do a festival and bring hundreds of people into the city from other places. Whatever, it is what it is. I just wish that the city could look and spend more time with other forms of creative art making that aren’t just murals. There are other things here. Not to shit on mural arts, because I love “Jingle” [Jaq Masters]. That stuff’s great. I just feel like there’s other things that the city could invest in.

Making Time has created a huge revenue stream for the city. It’s in the national press, and brings people from other places, all over the world, to spend money in this area. Same with music events elsewhere. Sometimes the neighbors don’t like it, but it’s a great revenue stream. So, how do you make a business case for investing in art? Do you need a PowerPoint? I don’t have a good answer for that either, but I just find that an interesting thing. How do you get the city to pay attention?

It’s like the thing I said about how I’m old and I don’t like putting my name on things. I’m pro-indie. I want to be independent. I don’t want corporate dollars. Corporate dollars are nice, but it waters down the art, so it’s hard to have your cake and eat it too in this department. There are ways, and I figure out a way. I get people to give me lots of money to make art. It’s fine. I just can’t convince things in Philadelphia to happen. Like I said, the institutions here… it’s hard. It’s a hard place for art and creatives in Philadelphia, especially with UArts [University of the Arts – Philadelphia] being gone now and know what’s going on with PAFA [Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts]. I’m frankly very worried about the creative class in Philadelphia and what’s going to happen with it. Yeah, it’s kind of weird, I’m not going to lie.

We were supposed to talk on Election Day. We all know what happened there. How are you, with that, and how do you think it will impact how artists make money and work?

Post-election, we’re talking? I mean, my reaction? I’ve been hugging my friends a lot, because it is kind of a bummer. It’s very sad. I always thought we were smarter than this, stupidly. Maybe I’m the stupid one. The future, who knows what the fuck is going to happen. I mean, I feel like activism has a place in art making and sometimes we gotta put on that hat, and if I need to go to bat to do things right, I will. We’ll see. I’m processing it in different ways. I really don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s very scary in that sense because arts funding already doesn’t make sense. It’s probably going to get worse, and when you engage in creating very… it’s like, the work’s a little heady, you know what I mean? It’s not for everyone, but it can be.

From a business standpoint, I have to say (and this is going to sound maybe insensitive, but who knows or cares?), all I know is that people are going to need… I think Dave said this best, and better than I could have, but we had a meeting right after the election about Mifflin and what happened this year and how we can continue the success of this last year into future years. He was like, “People need us now more than ever,” and I really believe that and I do feel that, and I think what I bring to the table, what I give back, is this escapism into beauty of nature and technology. That’s who I am, that’s what I do.

Unfortunately we’re going to need a little more than that [Laughs], because there’s going to be a lot of stupid happening that I sadly feel powerless against. That’s the shitty part of the shit sandwich here. It’s just like… the idiots won, so now what do we do? “Ok, you burn it down. Go ahead. We’ll build it back up, but you can fucking burn it down, because I’m not going to fucking burn it down.” Sorry, that got dark.

We will need you folks more than ever. It’s not nothing because people need to be fortified in order to fight. Community is so important – mobilizing and finding your people, but also finding the strength of, ‘What are you doing this for?’ When you’re dancing in a room it might not seem important, but it’s life!

We’re here to celebrate life. It’s always about celebrating life and humanity. That’s why we make art, that’s why we like art. Now is an important time for Philadelphia to stay weird. Let Philadelphia be a weird bubble and let’s get to work. What we can do is keep Philadelphia weird and keep it cool. That we can do, so I’m here for that. Let’s keep it weird cuz it’s all we got.

KEEP AN EYE ON KLIP COLLECTION BY CHECKING OUT INSTAGRAM & THEIR WEBSITE FOR UPCOMING WORKS AND LOCAL EXHIBITIONS (LIKE PASSAGES IN PHILLY & KLIPXXI AT THE BOK BUILDING, TONIGHT, FOR FREE).