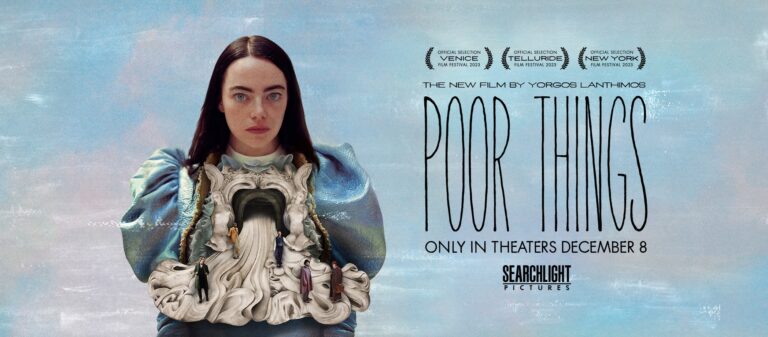

In Praise of Poor Things –

I know I’m late the party on this, but Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things is a masterpiece of filmmaking, writing, cinematography, acting, and editing, and having just seen it, I needed to write about it.

Spoiler alert (hinted in the opening paragraph): Poor Things is the best film I have seen in some time. For originality, it is right up there with recent films I have written about here, like the brilliant satire JoJo Rabbit, which I praised in this space in 2020. I do not often comment on movies or music or much art here, although I do in other places in this publication and in my books. The fact that I am infiltrating this column with a glowing review should give you some indication of how much this film kicked my ass from the opening frame.

Emma Stone, its female protagonist and beaming metaphor, is fantastic. Playing its central figure as visual/imaginative chronicler with defiant absurdity, rightfully took Best Actress in the most recent Academy Awards that for some reason also saw fit to bestow a ton of awards on Oppenheimer, which was painfully unoriginal in every way Poor Things succeeds. Shit, Barbie, a stellar contemporary satire on women’s plight in a fucked man’s world was better than Oppenheimer, which while a weaker depiction of this fucked world, does kind of present the same argument.

I digress.

While Stone appears in nearly all of the scenes due to the film being shown to us through a looking glass into her untainted, feral eros world, the rest of the cast, just as pertinent to its themes, shines as well. Especially Mark Ruffalo, as her boorishly feckless poseur of a social/sexual mentor, who, like Ryan Gosling’s wonderfully portrayed clueless, Ken in Barbie, travels a rapidly paced arc downward into despairing madness in a veiled comedic attempt to live up to his own self-aggrandized façade. This is also true of Willem Dafoe as the mad scientist, whose monotheistic name and machinations evokes both dread and empathy.

A quick synopsis of the plot, which does not do it a scintilla of the justice it deserves, is thus: Dafoe’s Godwin Baxter, mostly referred to as God throughout, (hence the monotheistic reference above) is a shameless take on Mary Shelly’s Victor Frankenstein from her groundbreaking 1818 novel, Frankenstein (subtitled The Modern Prometheus) who fishes a fresh corpse from a suicide out of the Thames to bring her back to life. Turns out she is/was pregnant, so Godwin, “a man of science” – a line which he utters constantly in the movie to excuse heinous deeds in the quest for knowledge, as his father did to him as a child – places the baby’s brain into that of the reanimated former Victoria Blessington and voila, our hero, Bella Baxter.*

*I will abstain from spoilers, as this is my attempt to get those who have not seen it to do so immediately.

The long and short of it is that Bella’s emotional and intellectual trek from impish id to impish id woman reflects humanity’s evolution of thought. This is aided in part by an interloping attorney, Ruffalo’s Duncan Wedderburn, who whisks her off into a world Godwin has been trying to shelter her from in the guise of libertine philosophy. Wedderburn ravages a willing Bella, who in her speedy maturity discovers her sexuality and like her insatiable appetite for anything the world offers, displays an equal fervor for coitus delights.

In fact, throughout, Bella’s personal quest to remain in a state of perpetual happiness, truly and without shame or guilt, literally and symbolically strips bare the hypocritical men she encounters; men obsessed with the failed pursuits of happiness in philosophy, religion, politics, and sex. Not that the awakened Bella does not dabble in those, oh, she does, as does the film’s most potent themes, but they merge as a mere pathway to fulfilling her most ardent desires, until she is made to realize she does not exist in a vacuum, much like children must learn eventually.

A few key elements separate Poor Things from merely a gothic coming of age story. Visually it bursts from the screen in both black and white and color, depicting, much like the legendary Wizard of Oz, a woman’s stark revelations on how life sometimes appears unreal. Using fish-eye lens, enormous wide shots, almost living impressionistic paintings saturated in colors, and relentless closeups, Lanthimos and his cinematographer, Robbie Ryan, keep us unbalanced – as if we are equally naïve and hungry for experience. We share Bella’s quizzical consumption of art, music, commerce, human nature, and the enigmatic architecture of city life as she travels through much of her evolution. She (we) can only comprehend so much of humanity’s fault-lines of jealousy, insecurity, anger, grief, and general confusion through her experience. She asks the questions that need to be asked and have been broached in treatises for eons but rarely penetrate our cycle of despair. We discover as she does. We grow along with her.

Added to these visual enchantments is the soundtrack. The music of Poor Things is another outstanding aspect of the storytelling – a dissonant and disturbing mélange that evokes an unsettled ecosystem from which the characters seem unable to escape. Its composer, Jerskin Fendrix, who describes his style as “electro punk” uses an impressionistic aural assault in the manner of such musical experimentalists as Arnold Schoenberg, La Monte Young, and John Cage. The music takes us inside Bella’s head, as her surroundings pummel it. As she emerges unformed and becomes more aware, using outside stimuli to develop her own voice, so does the music. Yet it remains discordant, as she always will be, as a manifestation of Shelley’s “monster.”

Speaking of Shelley, there are yummy asides to the author, culled directly from the 1992 novel by Alasdair Gray. Firstly, its late 19th century setting – more pointedly in the name Godwin, taken from the Shelley’s own father, political philosopher, William Godwin, whose complicated relationship with his daughter after the death of Shelley’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, a devout early feminist, was a huge influence on Frankenstein. Wollstonecraft’s late 18th century book, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman also reveals much of the themes in Poor Things, as does Shelley’s marriage to radical poet-philosopher, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and her relationship with libertine poet, Lord Byron.

There are so many layers to Poor Things; it is impossible to dissect here and certainly improbable without spoiling much of the latter half of the film’s narrative. It is, as I wrote to a colleague moments after seeing it, a heady mash-up of Frankenstein meet Siddhartha meets Anaïs Nin. And in modern Hollywood, where originality goes to die, that is some juggling act.