The New Jersey-born electronic producer is a film scorer by day, a scientist of modular synths all the time, and having a big year for music. A short followup to their first record A Day In the Life of the Mind, a new live album A Performance In Celebration of Solitude releases on Bandcamp today with a music video debuting here exclusively for AQ.

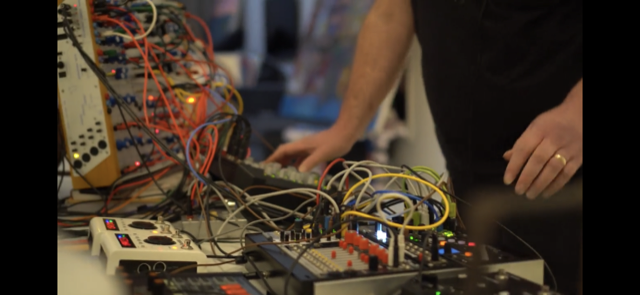

When I first meet Josh Ascalon over Zoom, he’s surrounded by synth modules. Swinging the mobile around for a 360º view, he shows the basement that serves as his studio in the two-story Brooklyn loft he shares with his wife and dog, Maxey. It’s “in shambles,” as it had just been flooded from our tri-state rains. (After we hang up, he’d continue the work of resetting it with all its oscillators, filters, amps, and sequencers, sprawling wires patching together circuits producing sound.)

Ascalon’s instrument of choice is the Buchla modular system (Buchla Electronic Musical Instruments [BEMI]), the 1960s contemporary to the more commonly-known Moog synthesizer. Favored for giving “musicians and composers enormous power to create unique, never-before-heard sounds,” the Buchla is a highly-customizable setup currently used by the likes of contemporaries deadmau5 and Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith.

Melodic, rhythmic, colorful, and textured, Ascalon’s modular, improvisational music is part of the electronic music (all is “dance” if you’re having fun) canon for its continued tradition of innovation and experimentation; he builds and modifies his own synths and often trades instruments within the community, creating new effects with foundations in New Jersey-core and Glasslands-era New York with notable collabs with Hooray For Earth, Das Racist (of “Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell” fame), and Chairlift (Caroline Polacheck’s band).

And he’s busy. For his day gig, he scored the Debbie Harry-narrated So Unreal and it was recently screened at the International Film Festival: Rotterdam. He just came back from Sundance for the premieres of The Rainbow Bridge and The Bleacher, the first films at the festival he’d composed scores for (he’s worked on three others credited for sound design and production) that will also show at South by Southwest this week.

Then, next week on March 17, he’ll open for Twin Shadow – longtime collaborator and founder of the imprint Cheree Cheree (home of his debut album A Day In the Life of the Mind) at Sleepwalk in Brooklyn. It’s all happening quite quickly, as just a bit before that, he supported the debut tour for Alan Palomo (aka Neon Indian) in his first-ever live performances as an electronic producer.

To prepare for those first shows, he’d spent two weeks at a converted barn turned seventies/eighties art studio for the first artist residency run by director/designer Aelfie Oudghiri. For documentation and posterity, he recorded the practice sessions. Today, these recordings release on Bandcamp as A Performance In Celebration of Solitude, the live album.

You can listen to it here, watch the music video premiering exclusively on The Aquarian below, and read our pre-show interview on Ascalon’s pioneering brand of modular music, the behind-the-scene leading up to these milestones, and a bit of his lived music history.

Tell me about the artist residency!

I was actually the first artist ever to do the residency! Basically, there were no guidelines; like a lot of “artist things,” you’re kind of in a weird almost camp-like environment with a bunch of other artists in some bigger space and the whole point is you’re just there by yourself and you get two weeks away from the world and just work on art. I took full advantage of it. It was an amazing experience. I just spent the time there working on music. I built synthesizers and stuff like that, so I was doing a lot of building of synthesizers.

All of the stuff I do, because I do music for film for work, [has] a difference. There is a difference between that and just like doing whatever-I-want music… making a record. There’s a difference. So I was able to do all this stuff that I normally would do in my free time, but just did it for two weeks straight. It was amazing and a really special place. It was great.

Did you have a plan or a list of things that you wanted to accomplish in that time as an artist who had that space then? Do you have a mindset for that?

For sure, yes. I had a very specific agenda. The first thing was building the sequencer I’ve been working on – a piece of equipment for my sets. The big thing was that I was booked for the two live shows, one in Philly [at Underground Arts] and one here in Brooklyn at a venue called Elsewhere, which are both big, 600-750 capacity places. I had really never done a solo electronic show. I used to be in bands back in the day, but I haven’t really performed in a long time and I didn’t know what I was going to do. I was asked to play these shows [Laughs] and I was like, “Yeah!” I started with that, but then I had to figure out what I was going to do because I didn’t want to use, like, computers. I didn’t want to do “computer songs” and reproduce the record I had just made and recreate that, because there’s almost no way of doing that without using computers and I just didn’t want to use computers.

Very much part of the reason I love modular synths and the workflow is that it’s so hands-on and so tactile that when I’m composing… like, I’m in my studio right now. I’ll give you a tour even though it’s messy [Gestures around the room]. My computer screens are here, and this is my synth zone, and it goes all all around here. I swear it’s not always this messy, but when I’m composing music, I spend all my time in the synth zone. It’s very different from the computer zone, which is a very different mindset. I kind of had some ideas of what I wanted to do [at the residency], but it was ultimately to prep for those [Underground Arts, Elsewhere] shows and really develop a workflow in which I could do a completely improvised set and a new way of creating music that wasn’t so composed, more organic and on the fly.

A lot of my recordings are done that way anyway. I don’t know if you’re familiar with multi-tracking, but basically it’s where you record one track at a time. In the act of recording an album, you do things one at a time, generally, unless you’re in a band and all in the same room or something like that. I record drums, then I record this one synth line, then this other synth line, and then I put them all together. A lot of that I do live, and one other part will be a live run of something, but then to put the whole thing together live so that you’re basically creating a composition completely on the fly… I purposefully kept my [toolset] very limited to something that would force me to be very creative with what I had. It’s a lot less than what I had in my studio, for instance, and it would force me to really get creative with the tools I was using. It was great because I recorded things just to document; I didn’t really record to work on an album or anything, it was just documenting the things I came up with techniques-wise – the techniques I was using to get certain sounds, certain rhythms, certain feels, certain modes, certain moods, and stuff like that. I don’t think they’re going to be used anywhere.

[A/N: These recordings, in fact, did end up being used! Please enjoy the premiere of the video accompaniment to the live album A Performance In Celebration of Solitude: DAY, out on Bandcamp today.]

There’s a world where I could do the live album now, we did shoot some video, but I don’t know if that will happen. We’ll see!

It was really just an exploration of how I could on-the-spot with a somewhat basic set of tools create a composition that’s interesting, that I think an audience would appreciate, and that is fun. Ultimately, it is fun, and it’s challenging because I imagine moving forward any live performances I give will be mostly improvised, but I will go into them with some sort of storyline or through-hole – sonically or technically. I’ll set up a group of circumstances that I’ll have to utilize for a performance and make the best of it, so there will be preparation in that, but what comes out will be different every single time.

I’ll have a general idea of what it’ll sound like [Laughs], but it’s not unlike jazz in a way, where you’ll have a chord chart or something like that but the players all improvise within that and do their own thing within that. At least right now, that’s what excites me the most. I don’t want it to sound, like, totally improvised, kind of B.S. music. I want it to sound compositional, but through the methods I’m using, it will be improvised but still have compositional elements that you can grasp onto, that feel that is melodic and rhythmic.

Great way to spend time in preparation for the Philly and New York shows. I understand you were born in Philly?

I was born in Philly, but I grew up in Cherry Hill. I lived there until I was 18 then moved out. I lived in South Philly for a while in my early twenties. I left the house and moved to “The Big City,” and kind of wandered from there. I have mostly lived in New York, but grew up in the Philly area for sure. It’s cool that I’m doing these two shows, because Philly and New York are very much my hometowns. They both have the same feeling to me as a hometown, so it’s cool to do these two shows specifically.

What have your experiences been as far as the music scenes – big shows, small shows, DIY scenes?

I mean, I spent most of my musical life in New York other than my formal upbringing. I was very involved in the Brooklyn DIY scene in the late 2000s, early ‘10s, which was a really, I think, special time to be in Brooklyn. I think I appreciated it at the time. It was kind of when the “hipster culture” was getting to the masses, and that culture was really coming from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which is where I lived. That’s where all the great bands that were coming out of, like MGMT and Grizzly Bear, and people who were great friends of mine that I saw all the time, like Twin Shadow and Neon Indian. You’d be walking around the streets of Williamsburg and be like, “Oh! There’s the dude from TV on the Radio,” or “There’s the dude from that band that came from that era,” and everyone kind of knew each other. Everyone sort of worked together in one regard.

I was running a studio [RAD], too, so I would work with a lot of these guys and there was just a really special feeling about that time, specifically that Williamsburg music scene then. They had great venues like Glasslands. There were the main DIY venues, like Glasslands, but also 285 KENT, Cameo, and all these other venues.

After MGMT exploded, they would come back and do a small show at, like, 150-cap person room at these places. It felt very much like a community. Everyone knew each other, and because of my position as an engineer and producer, I got to work with a lot of these guys, work on a lot of great records with cool people – like Caroline Polachek who is now huge and blowing up like her old band Chairlift. I used to work with them. These were all just our friends and the people we knew when we went out on the weekend (or, not the weekend – we were out all the time). These were the people we would just hang out with and run around with and it was cool to see them kind of expand out from our little Brooklyn scene to become national/international acts. A lot of them are still very active today. It’s cool.

It was kind of a blessing and a curse, because we had that time and because Williamsburg was known for being such a cultural hub. I mean, we can get into a conversation about gentrification, but that’s obviously a much more complicated topic because obviously it wasn’t always a white hipster neighborhood. When I was there, it was a neighborhood that the musicians could afford to live in, which is a big deal by the culture. The generation before us – Interpol and The Strokes and those kinds of New York bands – kind of created that culture and then this next generation of bands I mentioned took the mantle and, I thought, did a good job with it.

As it became such a cultural hub, like I said, it was affordable for musicians. That’s why we lived there. That’s why all the venues popped up. There were these industrial spaces that were vacant for years. Then once it was established as a cultural hub and “safe” and all this stuff, the developers came. Literally, just within the course of like five years, they paved over the entire thing with condos and completely priced out a large part of the creative class of New York that all lived in that one neighborhood. Ironically, the building that used to house the venues I’m talking about, like Glasslands and 285 KENT and Death by Audio, they were all in the same building kind of on this one corner. That’s where everyone went. You could just go there and there’d be something awesome going on at at least one of those venues every night. Vice bought that building! Vice started as, like, a skater/counterculture magazine and stuff like that. This is when they were expanding to a billion dollar media company. They bought that building and I was convinced they were gonna keep Glasslands. I mean, that’s an institution they’ll probably like, in there, you know? No, they just kicked everyone out.It’s just so, so ironic to see. It’s almost poetic.

The thing that really kind of helped raise the culture that we were all cultivating and a part of had become so big and successful, I guess, and became such a money-making, corporate entity like anything else that I had the naivety to believe that, “Oh, it’s Vice, they’ll respect the sanctity of these institutions of music in this neighborhood.” It was almost the day they took over and they just gave everyone the boot; all those venues closed.

Serendipitously, the people who ran Glasslands, which was always my favorite as I’ve been playing there in multiple different bands and stuff like that, and the final owners really did a great job of kind of fostering the community and stuff. They also ran a booking company called Pop Gun Booking. They opened Elsewhere in Bushwick, which is the show I’m playing at in Brooklyn. It’s the same crew, moving with the times of New York. Glasslands was very DIY – art installations and that kind of vibe. It was great, but it was definitely a bit grimy and the bathrooms were disgusting and all that, but evolving with the city itself, Elsewhere is big and they have multiple rooms. There are dance clubs, they have rooftop parties. It’s not DIY anymore, but because of what they did to cultivate the community, that community is still very much alive there. I think people still really like that venue. I’ve seen a couple of shows there and it’s been great.

It’s cool that it’s a different time and they evolved and it’s a club people come from Manhattan to Bushwick for, which wouldn’t have been the case with their original space. Nothing like that really existed when I was there in that time.

That story has made me so sad, but that ending made it better! There’s a new album out from Alan Palomo [aka Neon Indian] called World of Hassle and this is the tour. I understand you’ve worked together before.

Alan and I became friends a long time ago at those days in Glasslands and 285 KENT. I worked on his last record as Neon Indian, Vega Intl. Night School. I remember one day we were at 285, and I forget what show we were at, but he was just next to me and goes, “You know, I’m thinking about going on a cruise ship to record some of my next record. Would you want to come and engineer?” And I was like, “Of course!” We actually went. It sounds amazing, but there was a pragmatic reason for doing so. His brother [Jorge Palomo] has become kind of integral to his band and his sound now. He is an amazing bass player, super trained, and one of the most talented musicians I know, but he had just taken a gig on Carnival Cruise ship. He had a six month contract or whatever, so he couldn’t come to New York to record with us in my studio. We had to go to him, and actually spent, like, 10 days on a cruise. I brought a little rack of equipment and we spent 10 days on a cruise ship recording music for his record. We’d obviously take our breaks and use the hot tubs and the pools and go around, you know, the buffets and stuff, so it was definitely one of the more interesting recording experiences I’ve ever had. Then, when we came back to New York, we worked on the record in my old studio. I did some instrumental stuff for the interludes that he used for the record.

We’re still best buds today. I mean, that’s why he asked me to do those shows. I didn’t work on his new record in any hands-on way, but I’ve heard every demo since the beginning of the process, which was a very long process. I just supported him and what he did. One thing I always tell him and have told him since I’ve known him is that he just has such amazing taste. I just say, “Whatever you think is good… just trust your taste because it’s good. As long as you’re happy with what you do, it’s gonna be good.”

There are very few people that have good enough taste to say that about – or kind of the opposite is true, like there are very few people that trust their taste enough to follow it and not try to adhere to anything else in the zeitgeist or something like that. He’s always done that and that’s why he’s one of my favorite musicians. He’s just very authentic constantly. He does exactly what he wants to do and what he wants to do is very cool.

Remind me the name of your old studio?

It was called RAD, like R-A-D, and, yeah, it was pretty rad. It was in the basement of a new construction apartment building. I would joke that if you blew hard enough, the walls would fall down – with all the construction out in that area all the time and that kind of thing. Those buildings around there, they would just get them up real quick and get a bunch of people to move in.

Bushwick is still pretty sketchy, and there were some artists and stuff living out there, but this was more of a luxury building, so they wanted it to have amenities in some way. Somehow, through my old partner there – George Lewis Jr. from Twin Shadow who put out A Day In the Life of the Mind on Cheree Cheree – and who I saw perform just last night, him and our friend Damon [Dorsey] got into a situation where he was able to build this studio out. He had it built by the company that was building this building so that we could be an amenity to the building, which wasn’t really a thing because once we got in there, we just ended up making it our studio. It was weirdly in the basement of this, you know, really tacky new construction apartment complex.

That’s awesome. So, congrats on the new record A Day In the Life of the Mind. I know you mentioned that you met Twin Shadow in Brooklyn. How did you work together before, and how did you become the first non-Twin Shadow release on Cheree Cheree?

I actually thought he was a huge dick-head when I first met him. I always tell people, “I knew George before he was Twin Shadow.” He had this old band called Mad Men Films (Again, we were all part of this community, so we would always go see each other’s bands and stuff like that.) and I remember he had to play this show at some venue in the Lower East Side that I don’t remember the name of. At the end, he asked everyone to come on stage and then there were like 30 people on stage and I remember it just being a nightmare for the people that worked at the club. Then I tried to talk to him afterwards, so we kind of knew each other, and then he came to see one of my old bands. I’ll never forget this, but I walked out of the club and we’d had a great show and everyone was psyched. There were so many people there and he’s sitting there, like on his motorcycle with his feet up on the handlebars and his arm around a girl and he just looks over at me and says, “Hey, man. Nice show.” Or like, “Good show,” or something like that. In that moment, I was like, “This guy isn’t an asshole, he’s just really cool.” He’s never changed. His persona is Twin Shadow and he’s been that since before he was Twin Shadow. He’s just a really bright, elegant, confident, fashionable person with great taste – and he’s a great guy and a great friend. That’s kind of like where we started, and then we had become friends through that and I produced a record by a band called Hooray for Earth that he had heard and loved. (That’s another band that I worked with a lot and was actually in for a while. They’re great. Noel [Heroux] from the band is active again. He was on Sub Pop under another name called Mass Gothic and now he’s doing Hooray for Earth stuff again.) George heard it and really liked it; that was at the studio, RAD, that we started in Bushwick. That’s how he invited me in because he liked that record, so that was really cool and that’s when we really started getting tight, within a year of us kind of like building the studio.

By the time we were opening, the Twin Shadow record [Forget] had just come out and literally overnight – like the next month – he was touring the world. It was really crazy how quickly that happened. It was the intention for me, him, and Damon to run that studio and he was just like, “I gotta…,” and we were like, “Of course, do your thing.” I did work on Forget a little bit, which I engineered. I did some producing and we did some collaborations. We have just been buds for a long time.

When he started the label [Cheree Cheree], it was really just to put out his own music. The story is kind of silly, but the hat that I’m wearing is a Cheree Cheree hat. He got one of these made and it was kind of just to be like, “Oh, I have a record label now,” but the label was just a means to do things himself, because he was really getting sick of the industry, the way it was running, the way labels work, and some of that. He wanted something that he could control more, so he started putting out his music under his own label. He would partner with people, you know, to facilitate things, but he controlled much more than he had before. Like, for instance, he was on Warner Brothers and obviously you have so little control over things at that level, and even before that 4AD, which is a great label but, you know… Anyway, he sent me a picture of this hat and we were talking about this record, and I was like, “Why don’t you put out my record?” Just totally joking. He’s like, “Send it over.” Next day he called me and he basically described the record in a way I thought no one would; he interpreted it in the way that I actually made it. It was a really weird thing to have made something he understood fully. He was like, “I wanna put this out. I want this to be my first release.”

[A/N: Please enjoy the premiere of the second video accompaniment to the live album A Performance In Celebration of Solitude: NIGHT.]

George been super supportive and I’m really thankful because just being buds for so long and then getting to work together in this creative capacity, putting together material and stuff like that for promotions… he is the kind of guy that whatever he puts his mind to like he can make happen, you know? He put in his mind to put out this obscure electronic record.

We’re all aware that this sort of music that I make is not, like, commercially viable in any way. We were very honest with ourselves when we started talking about putting the record out. We were just like, “This is going to be like a very slow burn. If I find an audience for my music, it’s not going to be the week it comes out when it blows up. The goal is, over time, people are just going to find it and we’ll just keep on pushing it, like, consistently. Until it finds its audience,” you know?

In a promotional video for A Day In the Life of A Mind, you talk to Twin Shadow about being a bit literal about the name of the album to illustrate the intention of the music, somewhat simulating “a day in the life of [your] mind.” How so?

I actually don’t think it’s an observation of my mind, in particular, but an observation of the human psyche in general, if we pay attention to it, the point being the constant fluctuations of state of mind, the constant evolutions and transitions. I knew I wanted to make music that didn’t feel very linear, that didn’t feel like it starts here and then it goes here then goes back anywhere. I wanted something that flowed naturally. Almost more like a classical composition or something like that. We’re constantly in states of flux. We’re constantly changing. On my record, there are moments of what I would consider very beautiful, pretty, serene moments. Then those transition into very anxious, dissonant, clankerous moments. I feel like if anyone kind of pays attention to what their mind is doing at any point, that’s what we’re all doing, you know?

You may wake up and be like, “Oh, it’s a beautiful Sunday morning and the birds are chirping and all that stuff,” but then you get a text from someone you don’t want to get a text from and all of a sudden you get this feeling of anxiety or this feeling of angst. Whether that be on a very small scale or kind of all consuming that could hinder your total day or life. We’re never in that, like, state of what they call homeostasis, right? We’re always in fluctuation. Our mind is constantly fluctuating, even to think that you feel a certain way or you are a certain person or something that, like literally moment to moment. We’re really changing our emotions. Our hormonal balances, our chemicals in our body are all constantly changing and making us feel some way due to stimulus and due to our own internal thoughts. I think everyone, if they’re paying enough attention to what’s actually going on in their mind, is experiencing varying states of mind constantly. Nothing really lasts and it’s just always fluctuating, taking on new forms and for the positive and the worse.

I think that’s kind of why I wanted to call it A Day In the Life of A Mind because I think it has… I don’t know what percentage would be good moments and what percentage of bad, but I mean, a lot of people have dealt with anxiety. I’ve had those sorts of issues in my life – not unique there – and everyone does to some degree or another. In some people’s life it hinders more than others. I’ve gone through periods where it’s hindered my life extremely and then sometimes where I just have a little anxiety that’s annoying. Those are all states of mind that, if we paid attention to it, are there. It runs the gamut from, like I said, serene and beautiful on a good moment to just absolutely awful and discordant and unharmonious at other moments. Everyone, if they’re paying attention, experiences life like that.

Did you go into creating this record with that concept in mind, or did it happen organically? On the other end of that, do you think you’ll further explore that concept or keep it as a parameter go-forward?

The music came first. I knew I wanted to do something that was constantly evolving and constantly changing and somehow fitting into each other. I wasn’t necessarily even interested in, like, a through-line or anything that conceptually would feel, like, my mind, a mind, one piece, or one mind, you know? I don’t think I would thematically; I think I’ve said all I needed to with that. That’s kind of also why I called it “in three parts,” like, you have different parts of the day. [Laughs] As far as compositionally… I think a lot of those things you’ll see in my show are pretty much entirely improv. A big thing that I’m into musically for this record and I think I’m still interested in very much is doing things that hint at being melodic or something like that, but just hinting at it.

Not to get too technical, but I use a lot of aspects of modular that basically create random parameters. There are random generators and stuff like that are essentially chaos machines just sending out control voltages all sorts of different ways. I actually use those. Almost all the melodies that you hear, if there is anything melodic on my record, is actually created randomly that I was able to harness enough through the use of my Buchla and other synths to make it feel like it was melodic or repetitive. If you actually listen, though, nothing really repeats. It’s constantly deviating. There might be a melodic line you hear, and then you’ll hear it again and you think it’s the same, and you might think it’s the same one, but it’s not. It’s actually deviating to varying degrees. Sometimes quite obviously and sometimes subtly so. That’s something I really like: the idea of non-repetitive sounds kind of giving the illusion that it’s repetitive – just enough to grasp onto.

At least in my mind, for something to grasp on to, you need that melody. You’re so used to hearing that, whatever that is, but it’s never fully giving it to you. It’s always kind of throwing you around it, but somehow giving you the comfort of pretending it’s there. It’s kind of how I see it, and I think that’s something that I really enjoy exploring. I could see that kind being a part of, like, a lot of my work moving forward.

The brain likes what it likes, and sometimes, it doesn’t know why.

Yeah, totally.

YOU CAN LISTEN TO A Performance In Celebration of Solitude & A Day In the Life of the Mind ON BANDCAMP. FOR MORE INFORMATION ON HIS UPCOMING PERFORMANCES, INCLUDING AT SLEEPWALK IN BROOKLYN ON WITH TWIN SHADOW ON MARCH 26, CLICK HERE.