The Beatles’ ‘Revolver’ Reappears as a Box Set

Can we pinpoint the time when the Beatles took their first giant step beyond creating extraordinary pop/rock love songs to chase even loftier ambitions? The answer is yes: it was April 1966, a mere three years after the UK release of their first album, Please Please Me, when the Beatles assembled at London’s EMI studios to begin work on Revolver, their seventh studio LP.

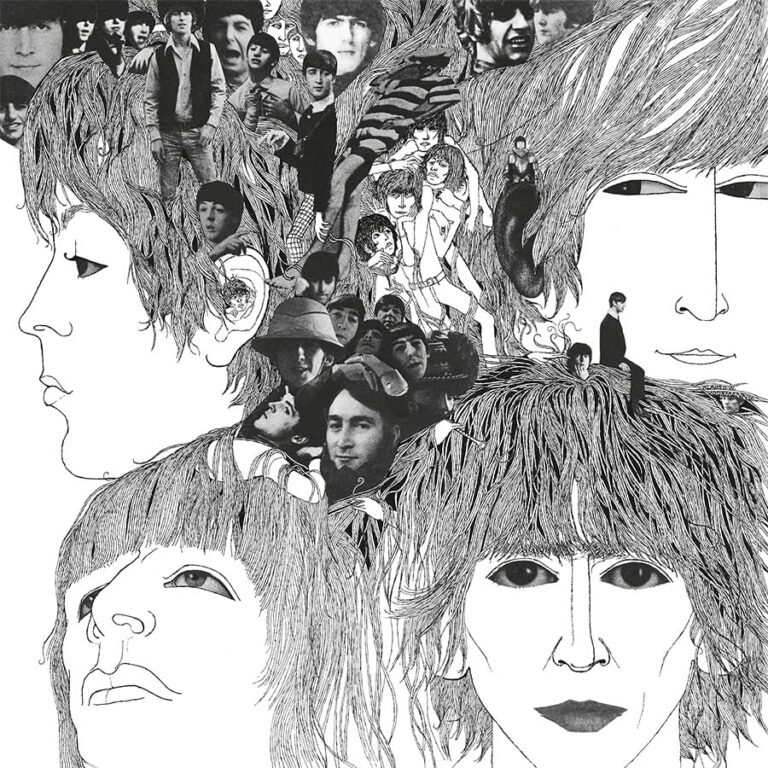

You can certainly sense their adventurousness in 1965’s great Rubber Soul, which employs such instruments as sitar and harmonium and features the Beatles’ most sophisticated arrangements and lyrics up to that time. But it is Revolver, which came out in August 1966, that finds the group moving firmly into a whole new world. Even Klaus Voorman’s iconic and Grammy-winning cover art signals that something has changed.

The album, which seems influenced by both psychedelia and Eastern philosophy, includes only two numbers with traditional-sounding love lyrics, both by Paul McCartney: the mournful “For No One” and the wonderfully melodic “Here, There, and Everywhere.” A third McCartney number, the brass-infused “Got to Get You into My Life,” sounds like another love song, but he has revealed that it’s “actually an ode to pot.”

Elsewhere, we have such tunes as “Dr. Robert,” which offers John Lennon’s portrait of a drug dealer; his trippy “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which begins by inviting you to “turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream”; “Taxman,” George Harrison’s acerbic look at the British tax system; “Love You To,” his first full-scale venture into Indian music; his bright but discordant “I Want to Tell You”; and “Yellow Submarine,” a whimsical singalong number with Ringo Starr delivering the lead vocal.

Somehow, it all hangs together, though what most of these tracks have in common is… practically nothing. As Paul McCartney writes in a foreword to the book that accompanies a new “super deluxe” edition of Revolver, “One thing I am always proud of is how the Beatles’ songs were so different from each other. Some other artists found a formula and repeated it. When asked what our formula was, John and I said that if we ever found one, we would get rid of it immediately.”

That attitude certainly pervades Revolver, on which the group discards conventions left and right. The production employs such techniques as looped and reversed tapes, multitracked guitars, and adjusted speeds. The instrumentation includes a string section, horns, tabla, clavichord, and vibraphone. Clearly, the distance between this album and the group’s early hits is vast.

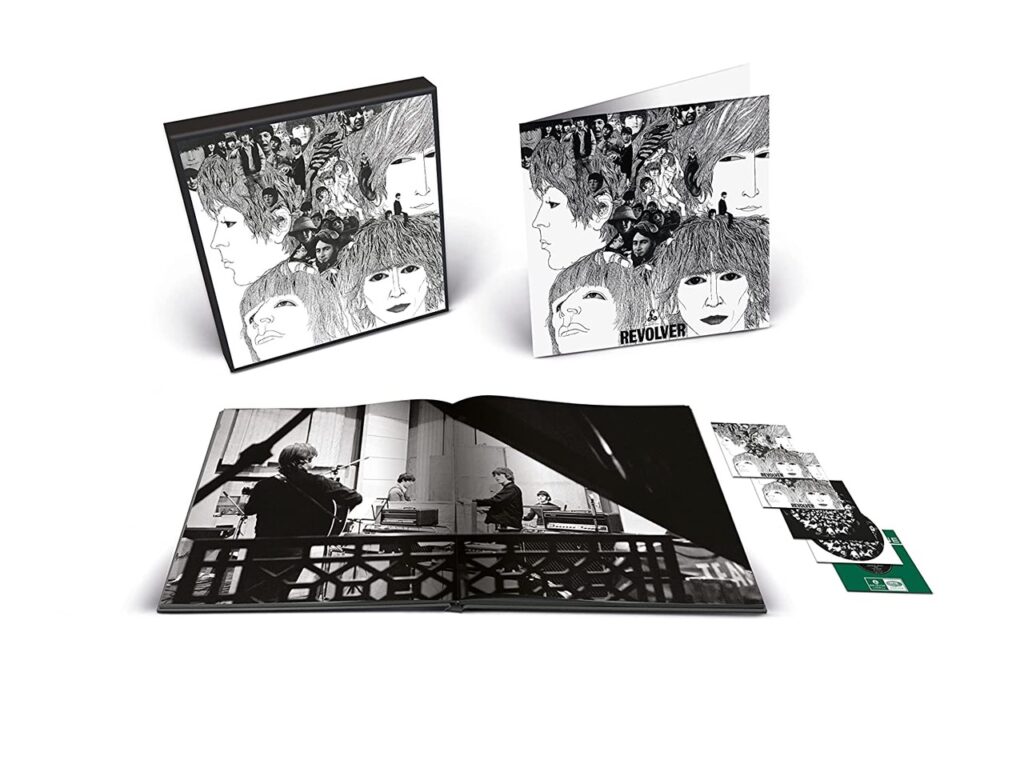

You can take an in-depth journey through Revolver in the new edition – the latest in a series of mammoth box sets that over the last five years has embraced Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, The Beatles(aka The White Album), Abbey Road, and Let It Be. Like those anthologies, this one was largely overseen by Giles Martin, son of the late Beatles producer George Martin. It features five CDs, plus a beautifully illustrated LP-sized, 100-page hardcover book that in addition to McCartney’s foreword includes an introduction by Giles, an essay by drummer and film director Questlove, and an article by Kevin Howlett on “The Road to Revolver.” You’ll also find credits and detailed notes about every track; a piece about Voorman’s cover art and illustrations from his graphic novel about its creation; a story about the LP’s reception; and notes about the roles of mono and stereo recordings in 1966.

Speaking of which: the set (which is also available on vinyl) devotes its first three CDs to Martin’s new stereo mixes and the original mono versions of the album and the non-LP single that resulted from its sessions. As the book notes, the mono versions were the Beatles’ priority in 1966 and are the key to understanding how the group “intended record buyers to hear their music when it was made.” And the differences between stereo and mono extend beyond the number of channels. To cite just one of many examples, the mono version of “Got to Get You into My Life” is 10 seconds longer than the stereo one and includes more brass instrumentation.

While rabid fans will be fascinated by such differences, even casual listeners are bound to appreciate the new stereo mixes. The music sounds noticeably brighter and sharper than before, and the vocals and instruments can be distinguished more clearly. The string octet on “Eleanor Rigby” practically jumps out of the speakers, as does the horn section on “Got to Get You into My Life.” Both tracks from the single – “Paperback Writer” and ”Rain” – sound particularly enhanced as well.

You’ll find more to like on the set’s two remaining discs, which contain 31 rehearsals, early versions, work tapes, and alternative mixes of Revolver’s songs. Granted, none of these recordings outshines the familiar ones (though a few are arguably as good), but the point here is to peek behind the curtain and observe the creative process. As you’ll hear, the Beatles took quite a few side trips on the road to the final product. A take of “Rain,” for example, shows how different it sounded before it was slowed down for the master recording. John Lennon’s acoustic work tape for “Yellow Submarine” – which begins with him singing, “In the place where I was born, no one cared” – seems less like a children’s song than an outtake from the confessional John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

There are a few things to grumble about regarding this release. Unlike all the other “super deluxe” Beatles box sets that have been issued in recent years, this one includes no Blu-ray with a surround-sound mix. (A Dolby Atmos version is available digitally, but that’s a separate purchase.) Also, you can’t help but suspect that the material is spread over five CDs to help justify the price tag. The total playing time is just over 162 minutes, which means this music could have easily fit on three discs or, with a tiny bit of cutting, on two.

Those gripes notwithstanding, this new edition of Revolver offers a superlative look at one of the greatest albums in the Beatles catalog and, in fact, in the entire history of rock.

Treasures from Lou Reed’s Archives

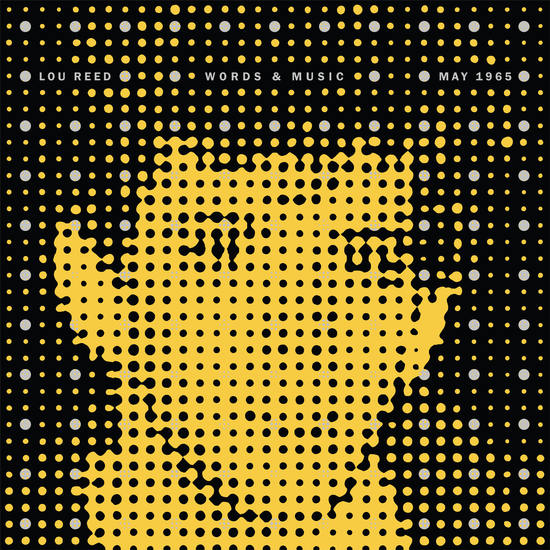

Given how much archival material has been incorporated into deluxe editions of albums by Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, you’d think the well would be dry by now. But it turns out there’s more – and maybe lots more, since Reed’s newly issued Words & Music, May 1965 is labeled “Archive Series No. 1.”

The disc delivers the well-restored contents of a reel-to-reel tape that was found in a sealed package behind Reed’s desk after his 2013 death. It presents 17 acoustic performances, many of them featuring accompaniment by his future Velvets bandmate John Cale. Most date from May 1965 but some come from 1963 or 1964 and one from as early as 1958 when Reed would have been just 15 or 16.

Included in this release – which comes with an informative 60-page booklet – are two versions of “I’m Waiting for the Man” and one of “Heroin,” both of which would show up on 1967’s classic Velvet Underground & Nico, as well as “Pale Blue Eyes,” with lyrics that differ dramatically from the ones on the Velvets’ eponymous third album. Equally intriguing are a variety of previously unheard or unknown performances. Among them are originals like “Stockpile,” a rhythmic, three-chord rocker that foreshadows such Velvets numbers as “White Light/White Heat,” and “Buttercup Song,” a lighthearted folk tune.

There are covers, too, including a variation of “Gee Whiz,” the 1958 Bob & Earl song, and – believe it or not – “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore.” Here, too, are Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” and an instrumental rendition of the traditional “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down” that the singer also apparently learned from Dylan’s recording.

Interestingly, Reed notarized the package containing these recordings and mailed it to himself (a so-called “poor man’s copyright”), and to further claim authorship, he introduces many of the numbers by speaking their titles and adding, “Words and music by Lou Reed.” He clearly believed he was on to something of value, and he was right.

Also Noteworthy

Trampled by Turtles, Alpenglow. Everything works on this effusive 10th album from Duluth, Minnesota–based Trampled by Turtles. The sextet has been together for nearly two decades, and in that time has honed a rich, cohesive, and frequently exhilarating sound. Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy produced Alpenglow and, if you know his group’s music, you won’t be surprised by his attraction to this outfit, whose recordings draw on folk and bluegrass but are rooted in rock. This CD, which prominently employs fiddle, cello, banjo, and mandolin, features 10 songs by guitarist and lead singer Dave Simonett and one (“A Lifetime to Find”) by Tweedy. Melancholy and regret pervade some of these numbers, such as “Central Hillside Blues” and the ironically titled “Nothing but Blue Skies,” but even the sad tunes are a sonic joy. As Simonett sings, “A song ain’t worth nothing if it doesn’t last.” These will.

Mali Obomsawin, Sweet Tooth. Free-form jazz and Native American music meld with folk and blues influences on Sweet Tooth, the first album from Wabanaki bassist, composer, and songwriter Mali Obomsawin. The engrossing, largely instrumental suite, which incorporates field recordings, finds the artist accompanied by a sextet that features drums, reeds, guitar, and cornet. Their consistently adventurous music, while sometimes redolent of artists ranging from Miles Davis to Albert Ayler to Oregon, is in a class of its own. An auspicious debut indeed.

Various artists, The Skippy White Story: Boston Soul 1961–1967. For decades, Skippy White played a big role in Boston’s R&B, soul, and gospel music scene as a record store proprietor, radio show host, label owner, and producer. This album – whose extensive liner notes include essays by the J. Geils Band’s Peter Wolf and journalist Peter Guralnick – zeroes in on a key era, with 15 excellent albeit little-known White-produced tracks. Among the highlights: Sammy and the Del-Lards’ sublime sax-spiced doo-wop called “Sleepwalk” (not the Santo & Johnny song, though the opening seems similar); the Motown-influenced “What Would You Do,” by the Precisions; and a blues number called “Georgia Chain Gang,” by Guitar Nubbit.

Jonas Fjeld, To the Bone. Jonas Fjeld, a major figure on the music scene in his native Norway, enjoyed international success with 2019’s Winter Stories, a collaboration with Judy Collins and the Americana group Chatham County Line that topped Billboard’s bluegrass chart. Back in the 1990s, also, he recorded two excellent albums with American singer/songwriter Eric Andersen (who lives in Norway) and the Band’s Rick Danko. Those projects aside, though, he has focused on recording acoustic music in Norwegian, so this album is as surprising as it is welcome. It’s rooted in folk, not bluegrass, and represents his first English-language solo release in more than two decades. On numbers like “Sansa’s Wedding Song,” which features piano, string instruments, and clarinet, Fjeld’s gentle melodies and warm, understated vocals are affecting.

Julian Taylor, Beyond the Reservoir. Julian Taylor’s last album, a pop/folk outing called The Ridge, found him writing exclusively autobiographical material for the first time. He continues that trend on the fine Beyond the Reservoir, which benefits from memorable lyrics, vocals as warm as Steve Goodman’s, and a terrific backup group that includes a string section, pedal steel, and piano. Taylor wrote (or, in two cases co-wrote) all the songs aside from the album-closing “100 Proof,” a sweet folk tune by Taylor’s friend Tyler Ellis that appears to borrow the music from Elizabeth Cotton’s “Freight Train.”

Jeff Burger’s website, byjeffburger.com, contains five decades’ worth of music reviews, interviews, and commentary. His books include Dylan on Dylan: Interviews and Encounters, Lennon on Lennon: Conversations with John Lennon, Leonard Cohen on Leonard Cohen: Interviews and Encounters, and Springsteen on Springsteen: Interviews, Speeches, and Encounters.