The most misunderstood song in pop history started out as but a mere deep cut off Leonard Cohen’s brilliant Various Positions album in 1984, his seventh studio LP, but the head of his label, the late Walter Yetnikoff, called the whole album a “disaster” and refused to release it. When cooler heads prevailed and the album came out in 1985, it was Bob Dylan who first covered “Hallelujah” by performing it in concerts.

It took a full 10 years but in 1994, the cultural floodgates opened up when Jeff Buckley’s version hit a nerve. Subsequent versions by U2, Justin Timberlake, Bon Jovi, John Cale, Popa Chubby, Celine Dion, Willie Nelson, Jimmy Osmond, Bono solo, Rufus Wainwright, and oh-so-many American Idol contestants made the song rather ubiquitous. k.d. lang nailed it live at the Vancouver Olympics. The Canadian Tenors performed it on the 2011 Emmy Awards telecast. TV shows like The West Wing, ER, The O.C., and House used it for particularly affecting scenes. Even children loved it on a simpler level when it was used in the animated film Shrek. VH-1 elevated it even higher when used as a soundtrack to its 9/11 coverage. Cohen even said, “I think it’s a good song, but too many people sing it.” Now there’s even a feature film documentary about it, Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song.

So what is it about this song that makes it all things to all people?

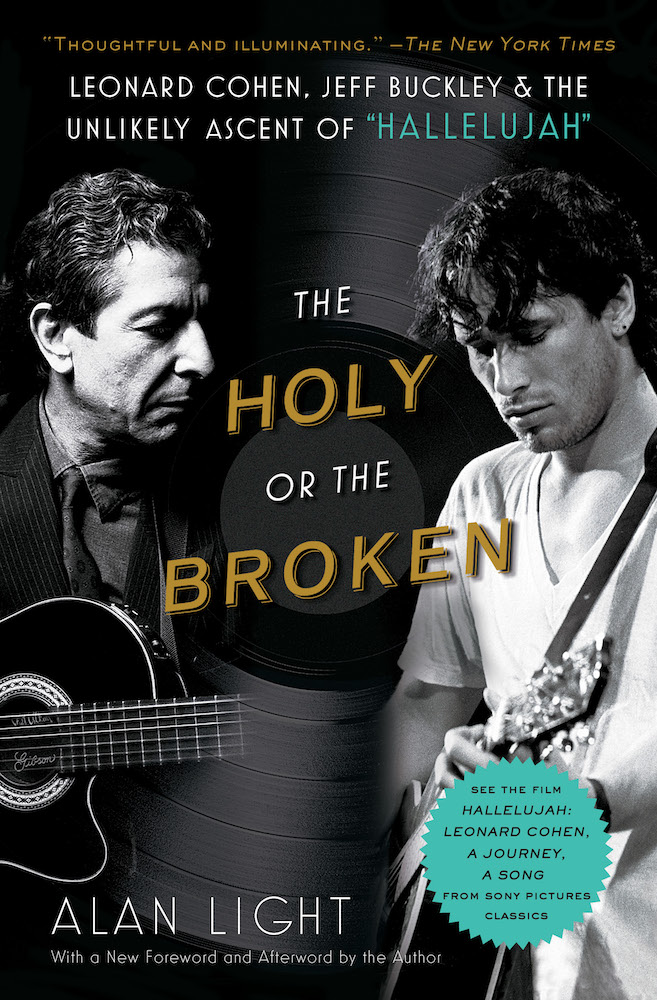

Alan Light answers this question sublimely in his eminently readable and totally enjoyable book, The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley & the Unlikely Ascent of “Hallelujah” [Atria Books/Simon & Schuster]. The author has written for Vibe, Spin, Rolling Stone and the New York Times. He co-wrote one of the best rock’n’roll memoirs of them all with Gregg Allman, My Cross To Bear.

Light traces the careers of both Cohen and Buckley to fascinating conclusions. Buckley, the son of esteemed singer-songwriter Tim Buckley, who died in 1975 at 28 from a heroin overdose, himself died in 1997 at 30 from drowning in the Memphis Wolf River Harbor. Cohen left the music business completely in 1993 to go live at the Mount Baldy Zen Center – for six years! – to become an ordained Buddhist Monk, giving up life’s pleasures to wake up before dawn, pray, clean, meditate, and serve the 86-year old Kyozan Joshu Sasaki (who died in 2014 at the age of 107). When Cohen came back, he discovered his trusted associate had wiped out his bank account. Firmly resolved to continue, he started touring late in life, made all his money back and more, and became an international superstar, beloved and respected. (Cohen died in 2016 at the age of 82 but not before recording one last haunting message from the grave in 2019, Thanks For The Dance.)

Light dissects the song’s various meanings through a prism of religion, culture, sex, and human foibles. Traditionally, “hallelujah” is a Hebrew word meaning “glory to the Lord.” Light’s title of The Holy or the Broken comes from Cohen’s assertion that it could also be, in Cohen’s lyrics, “cold and broken.” How could those who sing it as merely a religious observance, understand lines like “she tied you to a kitchen chair/She broke your throne/She cut your hair/And from your lips she drew the Hallelujah”? Or the purely sexual line “I remember when I moved in you/And the holy dove was moving too/And every breath we drew was Hallelujah.” Thus, Hallelujah as orgasm.

There’s just something about his melody, his use of that one-word chorus, and, of course, the opening “secret chord that David played to please the Lord/But you don’t really care for music, do you?”

Alan Light has accomplished the improbable. He wrote a whole book about one song, interviewed dozens of artists, took apart the various meanings, put it in the context of the times, and his tome turns out to be a well-researched detective tale of epic proportions.