Older musicians typically coast along doing their craft with little impact. The more successful senior musicians become legacy artists, reveling forever in the more glorious days of their youth. James McMurtry, on the other hand, turned 60 years old this past March and, amid very little public fanfare, continues to be at the peak of his game. He is barely known in the larger mainstream, yet those who do know his work bow before him in respect.

James McMurtry’s dad, Pulitzer Prize and Academy Award-winning novelist Larry McMurtry (Lonesome Dove, the screenplay for Brokeback Mountain), gifted his son with a guitar when the boy was seven. Mom, an English professor, gave the youth his first lessons. The younger McMurtry began writing and performing in his teens. He became a lauded songwriter, cross-pollinating in the Americana, country, and folk rock fields. His uniqueness is in the penetrating observations of ordinary life that he sets to lyrics and melodies. He apparently inherited and developed his parents’ literary skill sets.

In recent years, the COVID pandemic paused McMurty’s in-person performances. As a temporary substitute, he performed a series of live streams from his home. This venture allowed him the opportunity to preview many of his newer compositions as unpolished works-in-progress. McMurtry eventually recorded these songs and released his 10th and most recent studio album, The Horses and the Hounds, on August 20, 2021, his first release in seven years.

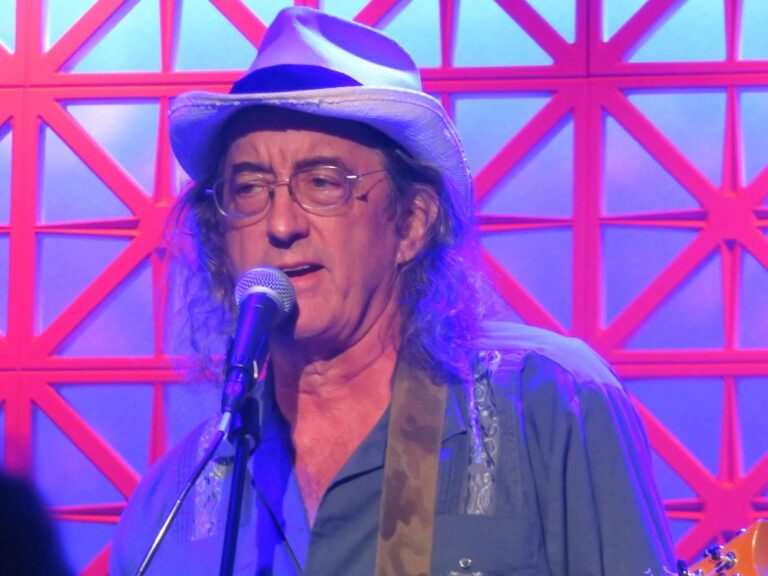

McMurtry has been recording his songs since the late 1980s, and at Brooklyn Made he performed songs from throughout his career. McMurtry sometimes tours as a solo act, but here he performed with his most faithful accompanists. McMurtry’s insightful and panoramic lyrical landscapes were driven like an engine by Tim Holt’s stinging guitar leads and accordion fills, as well as the uptempo support from the rhythm section, bassist Cornbread and drummer Daren Hess.

McMurtry introduced “Lights of Cheyenne” by telling the audience that if they get over to New Jersey and drive on Route 80 for a day and a half or two days, they would drive right into the middle of the song. This was one of only two songs that he performed solo, accompanied by his acoustic guitar. (The other solo performance was “Blackberry Winter,” on which the audience chanted with him the repeated line “To tell you no.”) Halfway through “Lights of Cheyenne,” McMurtry moved to the edge of the stage and closer to his audience, continuing the song without a microphone.

Well, I’ve been up all night and I’m down on my back

Workin’ the counter to take up the slack

‘Cause the money tree’s light and the whiskey stream’s low

You ain’t worked a week since July

You say the gravel pit’s hiring after the first

But you don’t have the nature for that kind of work

You might get hired on but you won’t make a hand

And I’ll still be here lookin’ at the lights of Cheyenne.”

McMurtry’s story lines were not constructed to reach satisfactory conclusions. They simply pictured fragments of life in middle America. Unlike an endearing Norman Rockwell painting, however, McMurty offered images that often reflected the perspective of a working-class character suffering hard luck or searching for peace of mind. Occasionally, one-liners in his song stung like a bee: “There’s more in the mirror than there is up ahead,” he sang on “If It Don’t Bleed.” Other songs demonstrated a wry sense of humor; on the chorus of “Ft. Walton Wake-up Call,” the 60-year-old referenced the aging process by repeating the line “I keep losing my glasses.”

For more than three decades, McMurtry has documented the maturity of someone well beyond his years. Now that he has reached his senior years, his work may be even more genuine. Meanwhile, as McMurtry carried on the literary lineage of his parents, his son Curtis is also trying his hand as a singer-songwriter in the Americana, country and folk rock fields. May the circle be unbroken.