In praise of High White Notes – The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism and a discussion with its author, David S. Wills.

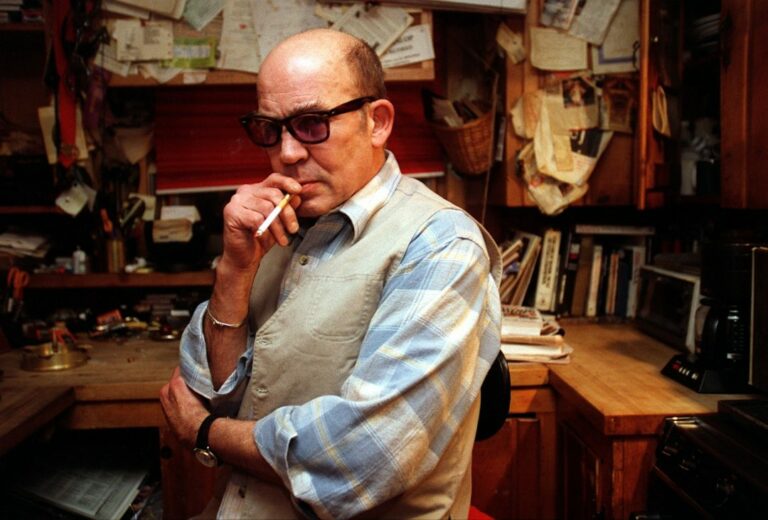

I have told this story time and again in this space: in the early to mid-nineties and then again in the early aughts before his death by suicide, I met and spoke with one of my most cherished literary and journalistic heroes Hunter S. Thompson, and in each of these brief but fruitful discussions I came away with an understanding on how much the myth of the wild Gonzo drug-addled, booze-hound, gun-toting lunatic overshadowed the serious, methodical ultra-talented wordsmith, a writer of such consequence as to be rightly called the Mark Twain of his generation. Thank you, David S Wills, who in the pages of his new book, High White Notes – The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism digs deeper and deeper into the brilliance of Thompson’s art and the natural inclinations he mixed with learned formation to come up with his finest work. Equally, Wills takes to task the times when Thompson sabotages his considerable talents, and lazily leans on repeating himself like a Las Vegas lounge singer toying with the melodies of the best of songs for mere schlock entertainment.

However, it is the music in Hunter Thompson’s writing that Wills reveals so masterfully in his book; sharing the Good Doctor’s finest achievement in the rock and roll era in mostly a rock and roll magazine to a predominantly rock and roll generation. It is the rhythm and meter of his most spectacular prose that we find the real Hunter, as it still sings its grandest tunes to us. And that is where, as one of Thompson’s mentor’s F. Scott Fitzgerald noted, the “high white notes” are hit – his early days as a serious journalist to his discovery of Gonzo and its off-shoots and deviations. It is a grand journey and Wills takes us there.

I spent some time with Wills a month or so ago when the book came out. Here is our discussion on his wonderful book, the mercurial nature of the literary titan that is Hunter Stockton Thompson, and what we can rediscover in his canon today.

We begin way back with the music of Fitzgerald…

David Wills: There is that famous story when Hunter was very young, typing out of The Great Gatsby (Fitzgerald, 1925) and it is a very important foundation for his writing. I can’t remember his exact words, but he explained it to a friend when he was young, about getting the rhythm. And then later in his life, anytime he talked about Fitzgerald, it was always the music of his prose, it’s the way it sounded, the way he captured the sounds of the ear. That’s exactly what Hunter was trying to do throughout his own career. And if you look at those brilliant moments, or what I’m calling the “high white notes” of his career, I think that’s when he absolutely infused his prose with that music. And I don’t think it’s an accident, I think he was aiming for that all along. I think he achieved that in things like, “the wave” passage from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and the “edge” passage from Hell’s Angels. And I think that’s why when we look at his later books, which I was very critical of, there are sentences and occasionally whole paragraphs where he did have that music, but, as a whole, he lost the rhythm of it.

There’s a reference in the end of the book about how he was really curious about learning why language sounds a certain way. He was trying to study poetics from a friend, because at first it just came naturally to him. And that, I think, comes from having read Fitzgerald and typed out Fitzgerald as a child, as well as other great writers, as well, of course, he was a big (Samuel Taylor) Coleridge fan. So, he read a lot of poetry, even if he didn’t write it. I think that kind of infused his very best writing with a musical sound.

James Campion: He loved Dylan, and specifically, “Mr. Tambourine Man” was a huge inspiration for him. Obviously Dylan conflated the art of poetry with music, the way Hunter might have conflated prose and verse. And then, of course, he writes about the conflicting radio playing one song in the car in Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas (1971) and [The Rolling Stones’] “Sympathy for the Devil” blasting on a boombox in the back. Also, the conflict of bringing in Doris Day into that book juxtaposed with the psychedelic drug culture, and some of the other music selections he introduces in Fear & Loathing on the Campaign Trail (1973). He was consistently infusing music itself into the wor, and this never really occurred to me in the way I just described it to you, until I read your book.

David: I’m glad. I wasn’t consciously thinking about music that much when I was writing it. I was aware, of course, as one of his famous quotes is something like, “music is fuel to me” and he would blast certain songs as he was writing, and people around him say it wasn’t just he was listening to music, he would listen to the same song or album, over and over and over…. He talked a few times about whenever he wanted the energy and inspiration, he would just blast out “Mr. Tambourine Man” on these immense speakers. He had a wall of speakers, that was just the most powerful thing because he didn’t have any neighbors around for far enough that you could get away with that.

James: I would say that you hit upon something that’s really important to understanding where Hunter lived as a writer. When I was working on my book on Warren Zevon, and, as you know, Warren and Hunter became close later in life, I was always amazed writing that book at how much Zevon was a closeted literary freak. He was always quoting books in his songs and how books inspired entire albums. He always said “Werewolves of London” was his answer to the Vegas book. I always felt like Hunter was a closeted rock and roll star, and in many ways, he did become one. I love when he finally admitted in the late seventies, “I have to sign autographs now, there are more people here to see me than Jimmy Carter” – and it negatively affected his way to write. He was trapped by this rock star persona.

David: He was conflicted about his celebrity. He would say, “Oh, I hate ‘The Duke’ in The Doonesbury Comic Strip.” (Garry Trudeau – 1970 to present) Sure, he probably did hate it to some extent, but whether subconsciously or not, he knew this was adding to his brand. He loved money, he wanted to make more and more money, and he knew that this contributed to this self-perpetuating cycle whereby he’s just growing more famous every year. And I think I mentioned in the book that I saw a photograph somewhere and it was on his “wall of things.” He was a very visual person, he needed to connect things when he was writing, but he had a wall of just pictures that were important to him, and on that wall was a Doonsbury comic strip, and I thought that would be very surprising if in amongst pictures of his son, and things like that, stuff that was really significant to him, he had this one thing that he supposedly hated.

Now, he did only say negative things about the strip in public, and yet, when everyone went at his house, he’d put on some wacky outfit, the Hawaiian shirt, his cigarette holder, he wanted to be recognized. He wanted people to see him and go, “There’s Raoul Duke, the famous crazy author!”

James: And you do point out that this, along with the drug abuse and alcoholism negatively affected his later work.

David: Yes. It became, in my estimation, cartoonish and unbalanced. When I’m reading Hunter – or really anything, but specifically Hunter – [I found] he was so tuned into certain words and how they work, I notice weird things that maybe other people wouldn’t notice, like collections of words that get repeated and themes that aren’t prominent. And I noticed when reading his work, there was a lot of, how do I say, surface stuff like “activistic” or “savage” and the use of drug names. And so, I wanted to go back and explore, ‘how did this develop?’ Because he wasn’t always the same person, the same writer. If you go back and read his very first writings as a teenager, you can start to see the patterns in the words and the themes starting to emerge, and I wanted to explore that, so I dug up everything I could find. Undoubtedly, I’ve probably missed a few things, but I think I’ve got 90% of it.

James: It comes through in your narrative. You can see the incline and the decline of his work very clearly in your book.

David: I felt his early work was interesting and worth exploring further because he didn’t want to be a journalist. He just recognized early on as a very well-read person – his mom preached the value of books to him – that he wanted to be a novelist. And then when he discovered [Ernest] Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Don Levy, and later the Beat Writers to some extent, he wanted to do what they were doing; write this revolutionary prose. He realized, “I’m a kid with no formal education, and I’ve got jail on my record, this long criminal record, what can I do? Well, I can literally only write, it’s my only saleable skill.” So, you get stuck into sports journalism, which he enjoyed, but I don’t think he viewed it as high art of any sort.

James: Right, but you point out this background gives him this unique ability to write action, which he uses in his best work, Hell’s Angels and Fear and Loathing, that he developed from being a sportswriter, which by the way Hemingway was and [Kurt] Vonnegut was, there’s so many great writers that started out being forced to describe action that was crucial to their development.

David: Yeah, and so you look at his later writing, and one of the weaknesses, I think, is that when he lost his physical mobility, and because of being trapped by celebrity to some extent his capability of mingling with other people, the action was gone. But yeah, he took those sportswriter verbs and then he turned it into describing motorbikes and cars and then this weird, violent prose. Soon everything was infused with this violence.

You go back to his early sports writing, and when he was describing the wrestling stuff as though it was real, like the guy had his neck broken, and it sounds so stupid. But then you look at his later writing, and you realize the satire, the subtle nod to “I’m saying fake things, made up things, with the intention of my reader knowing, but without me saying explicitly that this is made up.” It was always there from the beginning. You can see the origins of Gonzo, which I always categorize as just this weird mixture of fact and fiction, as I’ve said many times, it was there from almost day one, which is kind of bizarre in that you can see he’s trying to make this, what he perceived as just shit journalism, into high art. He’s also writing these short stories and these novels at the time, which he was convinced were going to make his fame and fortune, but then the end, of course, it was the mixture of that fusion of “literary journalism” that made him famous. And no one ever really did it that well, and no one’s ever been able to replicate what he did.

James: Yeah, I’ve always said that there is no Gonzo Journalism, there’s just Hunter Thompson. I think one thing you point out in the book is his unerring sense of humor. That was what drew me to him, like Twain and Vonnegut; I laugh out loud when I read Hunter’s work. That’s not the truth with many writers, even the ones whom he worshipped, like Hemmingway, who did not write “funny.” Hunter also loved to use humor to topple people at the top, but specifically people with money, which reflected what Fitzgerald wrote about in Gatsby, wherein he wasn’t accepted – he was the “new money” and you get that from that great article “Why Anti-Gringo Winds Often Blow South of the Border” (1963), the guy hitting golf balls into the Barrio. And then later you have Louisville Gentry in “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” (Scanlon’s Monthly – 1970) and the Blue Bloods in Las Vegas pissing away money while people are starving and dying in Vietnam. He’s constantly bringing it back to the “haves and have-nots” and he does it so effortlessly, but he’s writing the same story over and over again, which you point out.

David: I think there are various themes, probably too many themes, that’s one of his problems is trying to cram everything into every story. But yeah, that’s one of the ones that was just endlessly repeated. And as other people have commented, he was just constantly trying to write The Great Gatsby for the fifties for the sixties to the seventies to the eighties. Even he would admit that in interviews, and sometimes in his stories, he was looking around, like, “Where’s Daisy now?” and “How can I replicate this image and this theme?”

James: The green light, and all that stuff, yeah.

David: Yeah – constantly, constantly. But he did have this immense ability to portray wealthy and powerful people in a shockingly negative light. That, as you said, stems from his own childhood and his feelings of inadequacy in Louisville. You can see it so many times through his writing. What I tried to do in the book was point out where he said and wrote things that are racially quite insensitive, but for him, wealth and racism were inextricably mixed. Whenever you see him attacking rich people, there’s always this element of, subtly or not, accusing them of being racist, especially when you see the Kentucky Derby piece. It really came out there. And, of course, this contempt for the native people – the rich Gringo smacking golf balls into this poor Colombian neighborhood; whether that ever happened or not, who knows? He just tied those things together and time and again, you see that coming out this, “Wealthy people are awful, racism is awful” and just bringing these together.

James: You cite what you feel is Hunter’s misuse of capitalization and ellipses and just odd phrases that are not proper sentences in the book quite a bit. It’s again, getting back to music, his changing the notes like Coltrane’s “Favorite Things” and it’s not necessarily right, but it’s right for him. But you point out, “Hey, man, this is getting a little silly now.” Did you study literature and grammar?

David: Yeah, I taught grammar at university for many years and actually wrote a few books about grammar, so I definitely have that sort of bias coming through. However, having spent much of my life studying the Beats and Hunter Thompson having always been my favorite writer, I have huge respect for people that can break the rules of grammar. But Hunter himself said, I don’t remember the exact quote, so I’ll just paraphrase, he says, “If you want to break the rules, you have to know the rules first.” I think that’s an immensely important thing that very few of the people that copy his style ever bother to think about. He started with an intuitive grasp of the language, then he studied the rules until he knew them inside out. And you can see that through his early journalism as he’s learning and getting better and better, and his writing becomes tighter and tighter, more and more grammatically accurate, then you can see in the early sixties, he’s he starts to say, “Well, this is the grammatically correct way. but this is a more effective way to do what I want to do.” He starts breaking the rules and he starts forging his own style. My contention was, though, that he had an immense grasp over language in the beginning, and later, as he got into the cocaine and it started to rattle his brain, he lost control. You can see I mentioned a few times how he was unable to keep control of the narrative. So, he would forget that he’d already said something, and–

James: Like the ESPN articles (2000 – 2003). I went back and looked at a few and you’re right about that.

David: And in The Curse of Lono (1983). He tells us three times the Japanese runners ran past Pearl Harbor. I don’t think he’s doing that for emphasis, he’d forgotten that he’d already said it twice – you can see this time and again, these mistakes. When you look at the grammar, you start realizing, later on, when the grammar gets worse and worse and worse, and these errors start coming around, it’s no longer a matter of emphasis. You’ll look at his sixties writing and he’ll capitalize a word to give it special importance, and I think that’s a legitimate technique and I think it draws attention to this word. He’s using the sentence fragments for importance and he’s using the ellipses for importance. Later, he loses that control.

Now, there’s an argument to be said that maybe early on the editors were exercising more control over his writing and making it more straightforward, but I don’t think that covers nearly half of it. You can see from his unpublished work that this same disparity exists. It’s just a lack of ability rather than a choice.

James: What was your biggest revelation about Hunter when working on this book?

David: I don’t know. There were so many myths that came up that just didn’t hold up to the slightest scrutiny and yet they’ve been repeated in articles and biographies. I don’t want to say anything bad about the biographers because they’ve all in their own way done a great job, but they just kept taking what Hunter said and repeating it as the truth. But it was very clear to me that whether he meant or not, what he said it was not the truth. I guess it was surprising to me just how much he fabricated about his own life and other things. Like the old expression, “never let the truth get in the way of a good story.” For instance, in Kingdom of Fear (2003), everything, in my opinion, was just bullshit. They’re all his biographical stories and he was called out by the New York Times Book Review in that he had the opportunity to really get into the important stuff for the first time, but he didn’t do it. And, you know, he was talking about as a child getting arrested at nine years old by the FBI. I remember even as a 20-year-old reading that and saying, “That just can’t be true.” And yet, again, and again, it is repeated as truth. I investigated and investigated and I couldn’t find anything to disprove it, but that’s the thing with Hunter; when he was lying, it was always the stuff that was hard to disprove.

James: What do you think is Thompson’s finest work?

David: Well, you know, people ask me this about Hunter and about [Jack] Kerouac and other people I’ve studied, and I want to name something really obscure, but honestly the classics are classics for a bloody good reason and with Kerouac it was On the Road (1957) and with Hunter it’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. You mentioned earlier about laughing – it doesn’t matter how many times I read that book or how many times I study it (and studying a book really ruins it for you in many cases) – but I go back to take Fear and Loathing apart line by line, word by word, just doing the closest of close readings, and I’m still laughing until the tears come. It’s just such a work of fucking genius.

James: It really is.

David: On so many levels, it’s just magnificent. That’s why the chapter on Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is so stupidly long in my book because there is so much to say, there’s so many levels to how brilliant it was.

James: I loved the way, getting back to Fitzgerald, you break down the word-number and meter and focus of passages in Gatsby and Fear & Loathing and how they eerily match-up; almost mathematically. It illustrates what we were discussing earlier that lineage of greatness and musical sound in the writing.

David: I’m glad that worked, because I didn’t want to get too into the technical stuff. I have a terrible memory, but when it comes to stuff like that, for some reason, it kind of sticks out to me. So, I would see a word or a phrase or even the number of syllables in the sentence and it just resonates. I usually start with, “So, in December of 1958, he wrote this, and that’s the same, and that’s why he’s doing that are on page 100. And something of Gatsby he’s got the same number of syllables there…”

James: I realized after reading your book, why those are my two favorite books. And having written about music for most of my professional life and almost exclusively in book form now, it all became clear to me. That, and the humor we spoke of earlier.

David: Yes, and above all of that, the fact that no one really understands Fear & Loathing in that way. It’s so funny on the surface level and I just can’t get over that. Having said that, I mean, perhaps his best work, just on an objective level, might be “The Temptations of Jean-Claude Killy” (Scanlon’s Monthly – 1970), which he wrote two or three years before that, and everyone talks about “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” as the breakthrough Gonzo work, yet just before he wrote that he wrote the Jean-Claude Killy piece, and everything is in place there, basically. He was essentially rewriting the Jean-Claude Killy piece in a more refined sense with a little less constraint. And then Fear and Loathing is the long version of “Kentucky Derby.” He found this template in Jean-Claude Killy that worked, so he copied it and he copied it. One of the problems with the rest of his career was that he just tried to copy that again and again and again. It’s like, “Okay, you can get away with it three times, but when you start getting into it more and more, it’s more noticeable and more repetitive.”

But just to give another layer to this answer, my favorite book was The Rum Diary, (1950s manuscript published in 1998) and it’s not a brilliant book like Fear and Loathing, which is technically magnificent, but The Rum Diary, from a purely subjective stance, and we are talking about the most subjective of subjective writers, The Rum Diary had a huge influence on me. When I read my early writing, I attempted a lot of fiction – I’m terrible at fiction, and one of the reasons is probably because I was just trying to copy The Rum Diary over and over. I re-read it in the research for this book and two things struck me. One, it definitely wasn’t as good as I originally thought, although I enjoyed it again. And two, I felt, “Oh my god, I was ripping him off so badly without realizing it!” The Rum Diary just ruined me as a writer of fiction back then. And yeah, I still love it for, you know, the books that we love. There’s not necessarily a good reason for it. Sometimes you just read them at the right moment in your life and they hit you in that way reading Hunter will do for all of us