Technology can help a musician create impeccable music on a computer, but how does one translate that music to a live performance before a critical audience? Black Marble, essentially a solo project of former Brooklynite Chris Stewart, is learning the hard way. Black Marble released a fourth album, Fast Idol, on October 22, and the question was if or how the music could come alive in the live context.

Stewart began his Black Marble project in the early 2010s when he composed some songs on his laptop. He played the songs for his friends in Brooklyn and they responded that they liked his songwriting, but thought the instrumentation warranted improvement. Advancing his project, Stewart found his inspiration from cold wave dance music he heard at a Brooklyn club. Stewart acquired two vintage analog synthesizers, found a collaborator, and started accommodating his lyrics to this electronic genre.

At the Music Hall of Williamsburg, Stewart sang and played guitar, with musicians playing bass and keyboards. Electronic programs filled the sound, both with waves of synthesizer flourishes and percussion. Stewart sang in a near-monotone baritone, distorted slightly with reverb, his melancholic vocal melodies riding simple electronic chord changes. Stewart’s icy vocals matched the frosty throbbing of his musical accompaniment. Intentionally, the stark and bleak-sounding music was devoid of transferable passion.

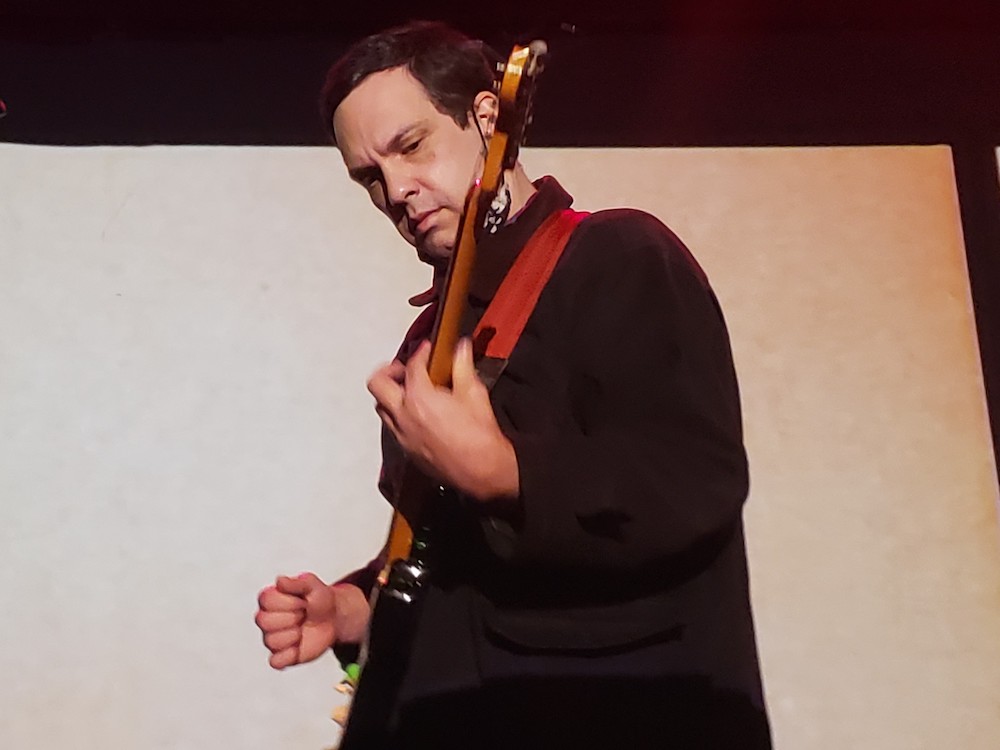

On stage, Stewart and his musicians were largely grounded to their positions, hardly moving. Stewart often sang with his eyes closed and he looked at his guitar far more than he looked at his audience. He seldom engaged his audience with insightful anecdotes or personable dialogue. His two supporting musicians played in near darkness, and depending on what was projected onto the screen behind him, Stewart was often in the dark as well. A disconnect was evident at the edge of the stage.

In all, Black Marble’s music was intriguing, but the performance appeared more like navel-gazing than shoe-gazing. Yes, watching this music as it was created live felt more exciting than listening to the recordings, but not by much. To take the music to the next level, Stewart must master the ability of moving beyond the original compositions and their instrumentation to a more audience-enveloping format. This will require a more connective approach than simply hiring a light show.