The line between art and activism is broader now then ever before, even if not fully understood by all just yet. Perry Serpa, in all his educationally-aligned, socially-aware glory, does understand, though. Therefore, he acted on it with a little help from his friends and a lot of inspiration from his musical days.

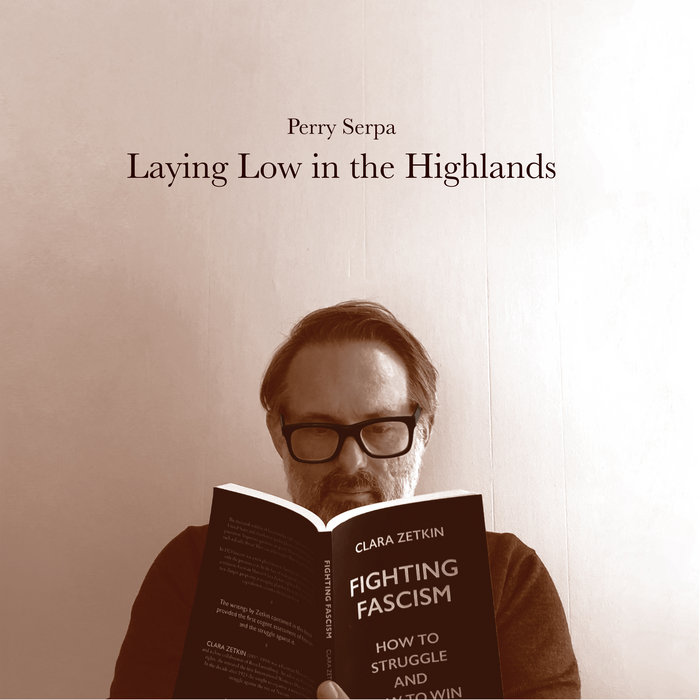

New York City has had its share of artists who burst through barrier after barrier, reaching the upper echelon of international superstardom. Then there are those dusky jewels, those Big Apple treasures, amazing talents who, for whatever the reason, remain local phenomena. Perry Serpa is one such cult hero. Since the early nineties, the Queens native has been creating peerless music first as a member of alternative rockers Lifehouse (not the popular millennial rockers) and chamber pop rockers The Sharp Things. Now he has ventured out on his own with Laying Low in The High Lands, a kaleidoscope of sounds and genres that he employs to express himself introspectively, as well as express his angst about environmental and societal ills. Aside from guest violinist Claudia Chopek and guest mandolinist/guitarist Ron Raymond, Serpa performs all instrumentation on the record.

Also an accomplished publicist (He started with Relativity Records and currently runs Vicious Kid PR), Serpa was inspired by activism while working with the Beastie Boys during his days at Nasty Little Man PR. (It was the firm’s receptionist’s greeting that inspired the Beastie Boys Hello Nasty album.) Today, in addition to music, the singer-songwriter is passionate about the environment. Serpa recently spoke to The Aquarian about his music, his activism, and our faltering world.

Conceptually, Laying Low in The High Lands is quite personal.

Yes, but it transcends the personal and moves into the consciousness of the whole country. A lot has happened to me during the last four years. The Donald Trump administration, for instance, ignited my spirit to react against it, but you have to express what you’re for and not what you are against, so this album is my last spurt of opposition. Also, I lost my parents in 2017 and 2018 [respectively]. The feeling of loss has been so prevalent that I’m only now getting used to it.

You lose a part of your soul each time someone close to you passes. You feel empty inside. At the same time, I, personally, had to take stock of what I still had: a family, a lot of nieces and nephews.

Losing our parents is something we worry about all of our lives. It’s out there down at the end of that road and you don’t know how you will accept it. Having now gone through the experience, I believe we have in our DNA the preparedness to deal with it, but it still hurts. When something good or bad happens in my life they were the first two people I want to share it with, but they’re no longer here – that’s why I covered Gilbert O’Sullivan’s “Alone Again (Naturally)” on the album. I remember hearing the song for the first time when I was seven or eight years old and it made me cry, because it was about a guy who loses his mom and dad. When I experienced their loss, that song found its way back to me. By covering the song, I, in a way, was exorcising it, getting it out of my system.

There is a great little record shop near my home and during the pandemic the owner would put shelves of vinyl LPs outside. The day after I finalized the mix of my cover, I walked over to the shop and in front of the shelf closest to its door was Gilbert O’Sullivan’s “Alone Again (Naturally).” If there is such thing as a sign, that was one. I had to buy it.

There are also songs about the pandemic, such as the instrumental “Out of Purell.”

That title occurred to me while I was in a Target in College Point [Queens], watching people scramble to get toilet paper, bottled water, and hand sanitizer. I went home and composed a much longer version. I shortened it and faded it out.

And it goes nicely into “Shadow of the Delacorte.”

Like the instrumental, it’s sort of an orchestral song, so they matched up. It’s about my wife and I and our son choosing to move upstate to quarantine and be miles away from the city, where all hell was breaking out. One of the craziest things was that there were morgues being set up in the park in my old neighborhood. How morbid was that?

The music on the album is so lavished and layered. Knowing you performed most of the instrumentation, I assume you employed a lot of synthesizers?

Although synthesizers were used on the initial tracks, I handed off the music to the lovely and talented Claudia Chopek, who I’ve known for more than 20 years. She’s played with me in The Sharp Things. She’s also played with Moby, Paul Weller, the Jonas Brothers, and Father John Misty. I gave her my tracks and she was able to layer them.

You’ve created this amazing piece of work, but in the world we live in, it’s difficult to get it out there. Are you concerned that all of your hard work, all of your creative expression, will become the proverbial “tree in the wood”?

No. I do this because I need to hear the music produced as it sounds in my head. You start to record the song and then you think, “It would be nice to hear French horn during this part.” That happens during the music-making process. It’s just me trying to express what is in my head. Then it’s about reaching out and pulling on people’s heart strings. It’s taken me a long time to hone that, to feel eloquent with that process.

The record transcends a variety of musical genres.

When we first started The Sharp Things, we were considered an orchestral pop band, and, dynamically, I was limited. When I was working on my solo record, at first, I didn’t realize what I was doing. I just knew I wanted to have all of these instruments on it. It has been an educational process making everything so lush and layered.

How did global warming and other environmental issues become another of your passions?

I have always been passionate about the power music has to evoke change. Back in 1996, I worked with The Beastie Boys on The Tibetan Freedom Concerts. I worked closely on that event for five years and it changed my life. It turned me on to a whole culture of people who knew how to argue and create change in a non-violent way. It influenced me to think of things in a different way. It made me see that the political needle could be moved by art, by creative response, by music, and by performance. People could see its purity and hear the messaging within it and be moved to make changes in their world. That feeling has always stayed with me.

Over the years as a publicist, I have become close friends with many of the artists I’ve worked with. As a musician, I understand them. I am able to communicate with them. I understand their struggles. As a publicist, it’s dealing with the media and the outcome is often unpredictable or arbitrary and it is an education for the artists. As a publicist, you foster them through that. You have to be there for them and you have to let them know that this is the way it goes sometimes and that it is not always in the right direction. Sometimes you receive amazing results, though. It is an experience that has informed my music and my other passions. Today I am trying to work the confluence of all of that and more.

Perhaps it’s because I am growing older, but I don’t have faith in music to change the world as it did during the sixties, seventies, and eighties. I do not believe music wields the power it once did.

I believe it still does. The problem is the multitude of platforms on which music can become mired. There is so much happening. There is the stratosphere of social media. People communicate in a different way these days. If you look at someone like Greta Thunberg, who is fighting for our future, and how that germinated from a kid standing outside parliamentary buildings in Sweden to become this massive movement, that couldn’t have happened without social media. I believe music is a part of that. It is easily plugged into the climate movement in effect and in action. Instead of one big concert happening, however, there are many things happening.

During the pandemic, there were many things happening like Climate Live. It was a livestreamed event witnessed in most countries. People just got together to make music for climate change. Because of these events, more and more people are having the conversation about the environment. We have been also emboldened by the Biden Administration, who has plugged us back into the Paris Agreement.

As much as social media has helped, it has also been hampered by the lies and misinformation that have been accepted as fact on Facebook and other platforms.

We, as a society, are in a precarious place. It’s very scary that we are about to go through what we experienced in 2016 and 2020 again during the mid-term [elections] and in 2024.

You have an environmentally-themed podcast, too.

It’s called “The Creative Climate” and was developed with The Climate-Control Project. Essentially, we use pop culture and music to connect people to the climate movement. The podcast explores that intersection. We have been interviewing those involved in the movement who are also connected to music. For example, there is a British organization called Music Declares Emergency and I interviewed its campaign director. I also interviewed Adam Gardner from Guster, who co-founded reverb.org, which endeavors to help musicians green their tours. It makes for great conversations when talking with musicians who care about the planet we live in.

PERRY SERPA’S NEW SOLO ALBUM AND NEW PODCAST ARE AVAILABLE WHEREVER YOU STREAM!