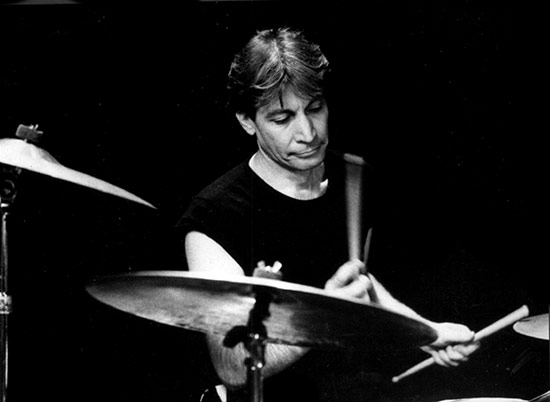

This special edition of Reality Check pays tribute to Charlie Watts and his now eternal greatness.

There are a few magical seconds that transpires in the 1969 Rolling Stones track, “Monkey Man” in which the band falls out and it’s just guitarist Keith Richards and drummer Charlie Watts that, for me, defines the essence of rock and roll. It has the requisite infectious rhythm, boy does it ever, the raunch, the sexual fury, the defiant bloodletting, and funky groove dynamic that would come to underscore what the Stones meant to the genre. There are hundreds of examples from hundreds of songs that might get you there, but that few seconds, from minute 1:48 to about 2:08, when Charlie pulls you back into the song by laying into one of his signature rolls that is epic Stones. In fact, screw it, listen to the song from 1:48 until Mick Jagger starts yelping like a maniac and marvel at Charlie’s incredible accents and fills from there on out and you’ll be just fine. It is why those who love this music, dance to it, fuck to it, imbibe to it, drive to it, and study it, always come back to it and the Stones again and again.

I use the word magical here because what happens with the Stones truly is. There is no viable explanation for Charlie Watts and Keith Richards, two disparate personalities inexorably linked – a perfectly balanced but oddly contorted element of what the right musicians can do when serendipitously tossed together in youth and purpose. A lot has been celebrated over the years about Mick and Keith. Rightly so. Songwriters. Icons. Pioneers. Sure. But for me, the Stones start with Keith and Charlie. I thought of Keith first when I heard Charlie died this week. Keith, of course, is the core of the Rolling Stones’ sound, beyond what the great and powerful, and dashing and famous – and honestly underrated – Mick Jagger could muster within this weird and wonderful construct, but Keith always said it was he and Charlie who fueled that engine. And it was always a strange engine that began with Keith setting the mean-streets groove, and Charlie bringing it home. When Ron Wood, member of other outfits long before he joined the Stones in 1975, came aboard, he marveled at how the Stones fed off the tempo of its rhythm guitarist and hung together on a tightrope by its drummer’s instincts. For awhile bassist Bill Wyman – also widely underrated in the annals of this classic outfit – held down the fort, too, but it was always a dangerously haphazard ride that could only have been anchored by Charles Robert Watts.

(For a proper tribute to Messrs. Wyman and Watts please dig on “Miss You.” Right now. Go ahead. I’ll wait.)

Watts did things in the Stones so miraculous that it was mostly overlooked for nearly six decades. Not overlooked as much as ignored. When he passed, the main plaudits for Charlie’s talents all over social media and in the music press centered around his steadiness, how he remained a classy lynchpin of non-showy drumming in the swirl of the Stones hurricane, how he was a metronome and a rock. And although all those things are true of Charlie Watts, they totally missed his most essential contribution to the Greatest Rock and Roll Band in the World. The Rolling Stones only ever existed beyond hit-makers and social pirates and institutional corporate touring machinery because of the unique just-a-tad behind the beat drumming of Charlie Watts.

Trained in jazz, he never stopped loving and revering its intricacies, which made you understand that his approach to rock and roll as a pounding forcefield was never his bag. He attacked it with subtitles and accents and nuances that brought diamond/snowflake qualities to the Stones canon. Watts’s drumming had no origin or a map. Charlie does not play “Honey Tonk Women” or “Brown Sugar” or thank goodness “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” like an in-the-pocket drummer might. He re-imagines that pocket and challenges the rest of the band to stick it out on his call. Keith starts it and Charlie wraps it up in his bow.

Watching Charlie Watts was the key to appreciating this. After being a Stones fan as a teenager, my first times seeing them – 1978 and 1981 – I suddenly understood the optical illusion of Charlie Watts, that little lift the sick off the hi-hat right when the thwack of the snare came down, the stuttered kick drum, and the rest of his quirky blues-funk-muddy-water-thud-punch. Supple wrist action, military style grip, the violent use of the crash as a ride when noise is needed.

His finest work may be on the band’s finest album, Exile on Main St. (“Rocks Off,” “Shake Your Hips,” “Lovin Cup” to name just three stand-outs), but it’s all there in the 1960s single phase, (“She’s a Rainbow,” a particulate favorite Charlie thang for me), after the blues cover band, and Chuck Berry tribute band phase, (“Route 66” – first song on the first album… ummm… wow), the pop phase (“Ruby Tuesday,” “Get Off My Cloud,” “Have You Seen Your Mother’s, Baby?,”), the revolution phase (“Holy crap, “Street Fightin’ Man,” right?) and the heroin chic fear-mongering phase (My god, when he kicks into “Sister Morphine”… fucking chills), that culminates in the greatest run of the era – Beggar’s Banquet through Exile – brutal beauty. It rattles walls and topples steeples, and Charlie is absolutely transcendent on those records and subsequent tours. Charlie may be the best thing about one of the most influential (and maybe best?) rock and roll live albums ever, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out. This is why he is on the cover; alone with a donkey, leaping off the road – an inside joke, since Charlie loathed touring. Loved the gig. Loved the two hours pounding away on “Midnight Rambler” and the rest, but hated the whole thing – the press, the gladhanding, the hotels, the constant movement. He’s a sitter. Drummers sit and make their mark. The other members move all over the place and pose for posterity. Charlie was a good sitter.

There is not enough space here to fully frame the man, (graphic artist, cartoonist, jazz band leader), so I concentrate on his drumming, which, again was so damn unique that when it was announced two weeks ago that the Stones were “replacing” him for an upcoming tour with an excellent drummer, Steve Jordan, I nonetheless whipped off texts to friends that it is a joke consider anyone beyond Charlie playing Stones songs. He is the soul of them, so much so that the trillions of cover versions over the years by bar bands and superstars sound like cheap imitations of imitations. No one can play Rolling Stones songs but the Rolling Stones, or (ahem), the Stones with Charlie Watts. I have written here a dozen times that there is no such thing as Gonzo Journalism beyond Hunter Thompson. People claim to practice it, but only one man did it. There was never any Minneapolis Sound, it was Prince and whatever Prince was doing with a bunch of musicians from Minneapolis.

Stones songs only exist in the realm of the Stones. No matter how many humans attempt to get the groove on “Start Me Up,” it is not, nor will it ever actually be “Start Me Up.” Quite frankly, I’m not sure what the hell it is or what the Stones are doing on that song to make it work, never mind appear to the untrained ear to be simple, but, trust me, it is more complicated musically than anything the prog rockers or fusion bands attempted to convince us was complicated to make a point about prowess.

Of course, because Charlie took a slanted view at simplicity in his playing, we all slept on the point this week on the plain fact that the man is a creative unicorn, the way Ringo Starr and Keith Moon, his contemporaries who got more press, were, and had forged for themselves within what those bands were doing.

For my money, though, I go back to two songs to put my own humble bow on this tribute to Charlie; the first is an obvious one: “Gimme Shelter” – the monster of all monsters in the rock realm. There is nothing that can touch it and Watts’s drumming on that is something out of Grendel. When he slams those accents in-between verses it fells me every time. Also, less known, is the 1981 Tattoo You track “Slave,” which may be Charlie’s finest moment. I think it is the best Stones song of the last decade they truly mattered, and for most of it they didn’t even play together. But “Slave” is Charlie’s Great Gatsby, his Mona Lisa, his lasting imprint on my favorite band of all time. It is less song than Charlie being Charlie. Unlike “Gimme Shelter,” the greatness is not in its composition but its execution, where all Rolling Stones songs came to be heard, conquer, and burn an indelible mark in our collective brain.