In Praise of Summer of Soul

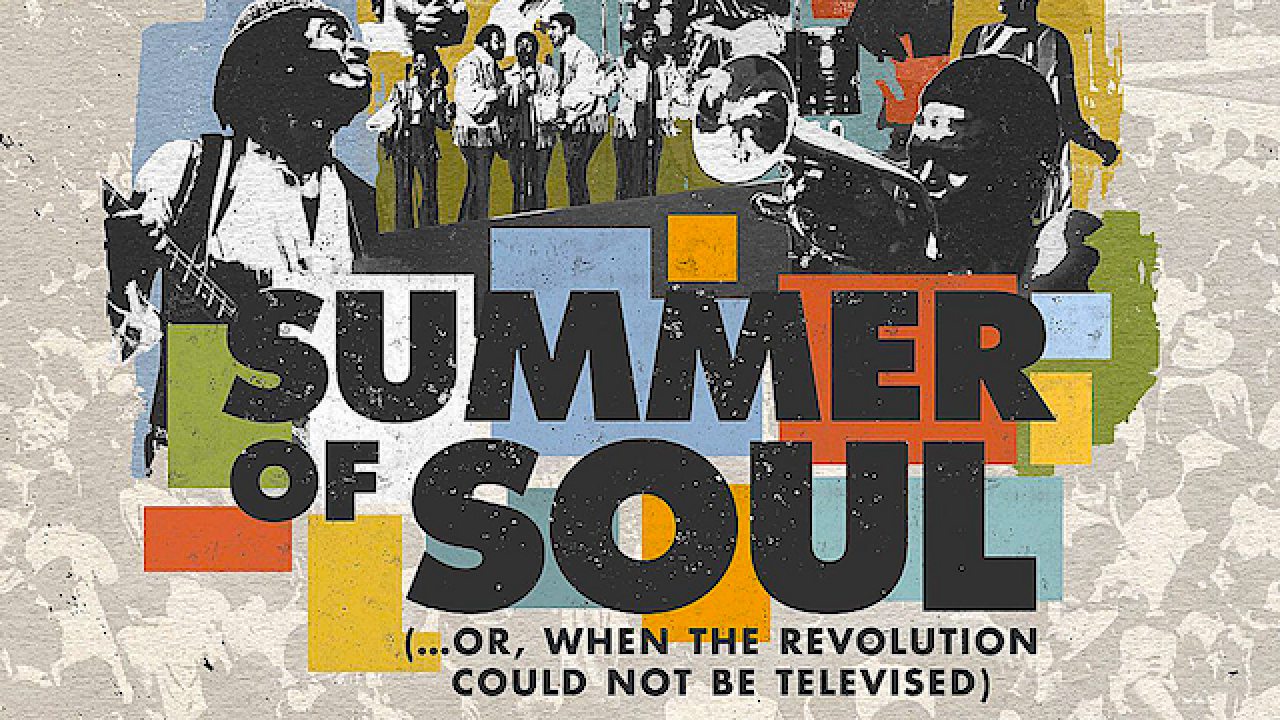

Musician and filmmaker Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson may well have made the seminal concert film of the age – the rock/soul/funk/gospel/blues American age. In his brilliantly engaging and crucially significant Summer of Soul, we get to simultaneously experience the culmination of our musical and cultural roots and the future of this nation’s sonic roadmap.

Thanks to my pal, singer-songwriter Eric Hutchinson, for suggesting we take this in at an actual movie theater (Imagine that, post-pandemic fans!) in the East Village this past week, I was mesmerized from the opening frames. The film launches with a fast-maturing, nattily attired Stevie Wonder sliding from center stage to ravage the drums. Suddenly, you are thrust into the moment – the heat, the excitement, the history. Summer of Soul literally brings to life long-lost footage from the summer of 1969, the absolute nexus of the pop world, a soul revelation from Motown to Stax, down the Bayou into the Baptist churches and Pentecostal revivals, the Delta Blues and the urban street funk and salsa searing rhythms.

Of course, the music isn’t the only theme of Summer of Soul. The voices – from the period and watching the footage along with us – proudly speak of community, faith, solidarity, and a relentless hope that permeated the audience and the performers that summer. Despite surviving a year of assassination, racial turmoil, and economic stresses, Black pride is indefatigable. Pride for Harlem, for New York City, and for the powers of youth and art to overcome the systemic bigotry of 1960s America. All the issues we endure today, captured in the stories of journalists, musicians, audience members, and from the stage.

There is a moment in the film that left me shuddering: Jesse Jackson’s memories of the very moment Martin Luther King was assassinated, one year earlier on that hotel balcony in Memphis. He describes King’s last words before the fateful shot, joyfully turning to bandleader, Ben Branch, who was to play at a rally that evening; “Make sure you play ‘Take My Hand, Precious Lord,'” his favorite gospel song. Cut to Branch playing behind the legendary Mahalia Jackson and an impossibly young Mavis Staples singing the song. Singing is not even a fair description. More like awakening the echoes of the holy rapture.

This is where Summer of Soul breathes; where its message drives deep – the music.

Unlike the film Woodstock, a documentary on the famous festival that took place during this run of shows at what was called the Harlem Cultural Festival that took place on weekends from June 29 to August 24 in 1969, Summer of Soul is a concert film in the truest sense of the word. While it does capture the zeitgeist of late sixties New York City, Harlem in particular, it concentrates on the stage. It is not an “experience” film of the event, as much as it reflects the talent, image, and influence of those who are connecting with the huge crowds – some 300,000 flocked to what is now Marcus Garvey Park that summer. Quick and essential shots of audience reactions grooving, weeping, shouting, and looking awestruck at what is transpiring before them adds to the allure of the story Questlove is telling. But it never interferes with the draw – the music.

Man, what music. In it, there is the very history of American song styles. And how incredibly young and vibrant the performers all appear. B.B. King is still smack in his prime as he tears through a fierce version of “Why I Sing the Blues,” a running history of the pain and anguish of the Black American experience that flows like a roaring river from its vocals down into King’s fingers, as he shreds his leads. Sly and the Family Stone, who will play arguably Woodstock’s hottest set within a week or so of their blistering performance here, are so incredibly mind-bogglingly killer, it gives credence to their massive cross-over powers of the time. Same goes for the 5th Dimension, riding high on their “Aquarius/Let the Sun Shine In” mega-hit, they nail it with such verve, it is as though they needed for the Black Harlem audience to embrace them. Watching an emotional Marilyn McCoo and her husband, Billy Davis Jr., watch themselves performing a half century ago is another of the film’s many highlights.

Questlove and his editor Joshua L. Pearson uncovered forty hours of film which was to be sold as the Black Woodstock, but was lost to time, until now. And why? How did this not find an audience? Many of the performers were primed to have incredible runs in the 1970s. Black audiences could be counted on to frequent theaters and support their music. It is a question the film-makers ask again and again.

If it is not obvious by now, I adored this film. It should be shown in schools and studied for years to come. The layers in its message and its music are crucial to our understanding of where we have been and where we are going. It is a cultural masterwork and entertaining as hell.

Bravo.