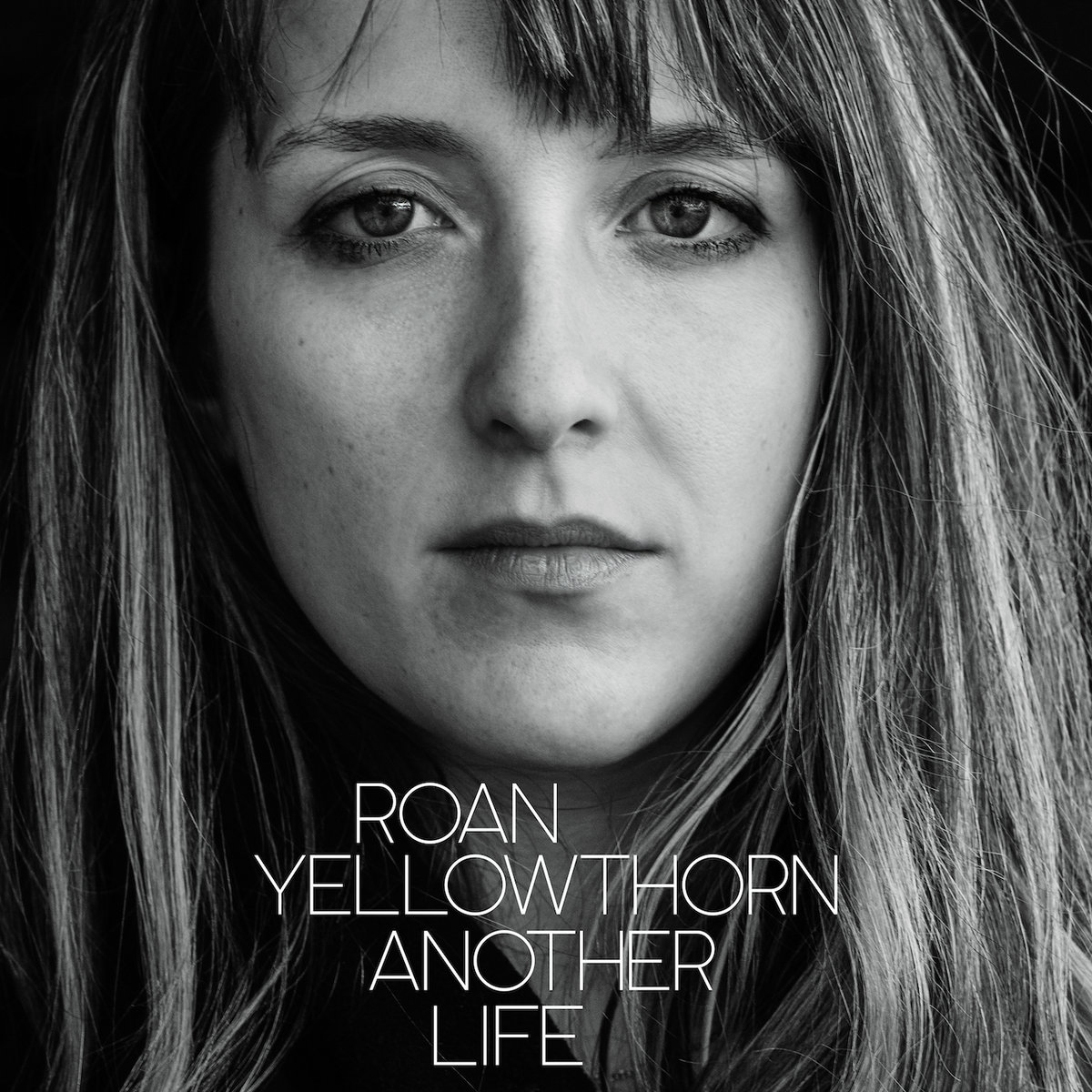

ANOTHER LIFE WITH JACKIE MCLEAN: Roan Yellowthorn’s lead singer and songwriter on growing up with her dad, Don McLean, coming to grips with a difficult past, being a mom, living her art and her newest, most confessional music.

She can’t remember exactly when, but Jackie McLean decided enough was enough.

One half of the married musical duo Roan Yellowthorn, its lead singer and main songwriter, and daughter of Don McLean (of “American Pie” fame), had taken self-flagellation beyond rationality in her art and her life. Depression, anger, and confusion had become dead ends. She wrote about them, sure, but there was no healthy endgame. They did not make her a better person, a better mom to her two daughters, a better wife to her husband, drummer and collaborator for Shawn Strack, or even a better artist. To do so, that stuff had to go. And at some point, her husband remembers, “Jackie goes into a room and comes out with a musical gem, and I ask, ‘Can I lay drums on this?’ And, luckily, she says yes.”

This is the origins of Another Life, the superb new album of strikingly confessional and cathartic songs by Roan Yellowthorn, which also aptly describes McLean’s journey and its eventual destination – past, present and future – to another life.

Another Life is quite simply the sound of Jackie McLean letting go.

“They were hard to leave behind,” she sings in the album’s opening track, “Acid Trip,” “But it was time to go / When you know you know”.

“Most of the songs on this album were written in an urgent, emotional state,” she tells me during our hour-plus-long, insightful chat. “In the summer of 2019, before the pandemic, when I was writing, I would go into a meditative state and mine my internal landscape for songs that expressed what I was going through. It was my way of processing feelings that felt too big to contain.”

Just as Another Life was completed, the 2020 quarantine closed the world. The entire project was all but in the can and ready to go before everything went sideways. So, McLean and Strack waited… and waited.

Throughout the summer of 2020, McLean began working on a novella. She sent me some pages. I was floored. It was a stirring tale of a young woman blossoming in college-age youth, while being crippled by guilt, fear, and self-doubt. The prose, original and earnest, reads with equal measure revelatory and combative, an acceptance of the pain in her past, while confronting its fallout. The main character is indeed her. She was remembering what it was like to live in a swirl of mental and emotional tumult, each page a new profession, a raw emotion conveyed. Not long after, I began receiving the tracks that would make up Another Life, and it all came into focus.

We spoke further about what triggered her ongoing recovery and how the art first inspired and then enacted it. I had to get to the bottom of these incredibly emotional and tender songs, set beside furious rage and pinpointed self-awareness. The sweetly melodic strain of the music sometimes belies the bubbling angst below the surface. The lyrics, however, take care of that. She sings in the “Bloodline”, a stirring song with an absence of ambiguity; “I haven’t felt glad in a long time / Why should I be / All the world is burning / Around me”.

It is the piano and keyboard sounds throughout Another Life that supply a deeper level to the emotive strains of McLean’s vocals. The backing tracks slyly bring the listener in, framing the heartfelt phrasing, which are balanced perfectly by Strack’s drumming. He plays them with loving desperation. He is right there with her. So much of the album’s differing rhythms help to keep these songs of longing and resurrection fresh.

All of Another Life’s songs tear at the roots of McLean’s unhappiness, the push and pull of keeping her unbalanced in the world, something she admits led to her emotional diagnosis; “Maybe five or six years ago, when my parents got divorced, my emotional landscape got broken open, and I was grappling with all sorts of old traumas, and new traumas, and trying to make sense of my existence; my experiences in the world, and for a long time I didn’t talk about any of it with other people, outside of Shawn. I did have a therapist on-and-off for a while, but I was busy trying to impress her with how together I was, to present a facade of someone who had it all together. But eventually it was the songwriting that allowed me for the first time to be truly able to explore in-depth how I was feeling. Only then was I able to own my feelings.”

McLean began sharing these experiences with friends and eventually the world with blogs on the songs as they came along, and eventually in interviews like this one. We spent so much time on the phone over the summer of 2020 pouring over much of what she reveals in Another Life that we thought maybe we should let her fans in. So… we did.

The following discussion was recorded with McLean lounging comfortably in a room in her upstate New York home in late May, a few days before the album dropped. Her voice barely registering above a whisper, it was riveting to watch her open up, finding comfort in her songs, her family, and her art.

Listening to this record, one cannot shake that it is a window both musically and lyrically into your soul. I know that sounds maudlin, but it makes for great art. And there is quite a bit here about your childhood or dealing with memories of your childhood. It starts with your relationship with your dad, Don McLean. Since your father is a famous singer-songwriter, did you have a normal childhood? Was he present in your life?

I don’t think it ever felt normal. I mean, I think that there’s definitely that element of whatever you’re in feels normal to you because you don’t know anything different, but once I was old enough to see the wider world around me, there was a huge dissonance between what I saw as normal in my upbringing and the outside world. I realized that what I had been conditioned to feel was normal when I was growing up. But it was anything but.

As far as my dad, he’s always been this huge, imposing presence; frightening, mostly. It’s hard to describe. But basically, I think, in my family, it was kind of always a situation where everybody was deferring to him and trying to make him comfortable and kind of wanting to stay small, so that he wasn’t made upset by anything. I can speak for myself to say that I was afraid of him. And I still have that feeling, even though I’m not anymore.

You never felt a comforting or familial connection to him?

It’s difficult, because on the one hand, you love your parents, no matter who they are. And I always loved him, you know, and I still do, but there was never really a feeling of acceptance and unconditional love there. That wasn’t really a prominent feeling. It was more like, “If you do these things, then I won’t be mad.” Everything felt conditional. I think that, over time, it led to me feeling like I wasn’t good enough and it negatively affected my ability to be accepted or loved. It all depended on what I was able to do or not do.

So, I assume this continued even after you had grown into a young woman?

Yeah. Here’s one example. This is just a kind of a broad stroke or whatever. But it was always, “If you get any piercings, or tattoos, you’re going to be written out of my will.” Or, like, “If you listen to that music, then I’m going to think that you’re stupid.” Very controlling.

Some may see this as “normal parenting” in a weird way, because parents do that all the time. A young person trying to express herself is often antithetical to how her parents see her. Sometimes that does come with conditions. I dealt with that as a kid and I grapple with that as a parent.

Now that I’m a parent, I can see that my dad was very anxious and not especially equipped to have children. Merely taking up space in his world was stressful. My existence was a threat. That led to a lot of emotional intensity, a lot of yelling and friction for every move … everything. Any normal part of growing and developing was met with anger and anxiety on his part. So, it was difficult for me to figure out who I was, and to even exist comfortably, because there was just this little space that I was supposed to occupy, and if I wanted to grow out of that, or be in a different place, or expand, then the message was very clearly you can’t do that.

All the songs on Another Life come across as a cocoon evolving into a butterfly in which you must break the seal to become free. No matter how old you are, or where you are in life – you have two children [Maya and Rosa],you are an accomplished songwriter in your own right, with a wonderful marriage, a home, you’re beautiful, smart, and talented, yet you still needed to break from that hold your father had over you to gain back the control we all need to be our true selves.

Yeah, I think an important part of being able to claim autonomy and being able to feel free is being able to express yourself freely and being able to move away from the constraints that were put on you by somebody else. I put this struggle into my songs… and they got me there.

I was very moved by the music video for “Acid Trip,” especially the footage of you as a child. In every clip there is this look on your face that either reveals abject joy or terror – and more than just the normal terror that children experience. There’s something in your face that’s troubling. Along with the music, it is a beautifully artistic expression, but heartbreaking. And then at the end of it, you’re a kid playing the guitar with a man in the foreground that I’m assuming is your dad.

Yeah, yeah.

Music was your introduction to him, because he’s a musician, and your first little steps of music is playing with daddy, and now you’re using music to break away from him. That must be emotional.

Well, the complicated thing about it is that when I was growing up, I can see now that he wasn’t like super famous at that point, but his status in our house was that he was the most revered person on the planet and nobody could ever compete with what he was doing in the world. And one way that I got positive attention from him was my singing. We would sing together at home. I would harmonize with my brother and music was something that we had in common. It was something that I got my first positive feedback from him on, which was a really good feeling, because there was so much either neglect or just dissatisfaction from him. Having musical talent was different. It gave me a passage to him that wasn’t available otherwise. Those were good times, playing music together. And then the weird thing that happened is that as I got older and became interested in pursuing it as more of a serious thing, he didn’t support that at all. He was very much threatened by the idea of someone else trying to be in his space that he had carved out for himself.

You read about this all the time with actors and actresses who have sons or daughters who want to go into the arts or show business; a part of it is the fear that they will have to endure the same crap they had to, but another side is they’re selfish, and they want to be the artist in the family. There is an element of ego in the artistic gene.

Yeah, but it was a very confusing thing for me, because I was like, “Okay, this is something I’m good at. This is something I’m getting positive feedback from, so I want to do more of it, and then at every turn, it was, ‘Don’t even think about it. This space is not for you. This is my area.’” That left me with a little bit of an identity crisis, I think, because music is my thing, but then I’m also getting the message that I can’t do it. So… what am I? Who am I? What am I supposed to be doing? Have I been doing the wrong thing all this time by focusing on music so much and feeling so musical? Is it not meant for me?

You eventually got there, even before you confronted these issues. You became a musician and a singer-songwriter, and your first album [Indigo, 2018] is an excellent example of your growth and seriousness as a musical artist.

It took me a while to understand that. I had to go through some changes, especially in college, where I was trying to explore other things just to see what else I could do. It kind of felt like starting from scratch all over again.

This is when you pursued writing, and your novella touches on this period of coming into your own through some travails.

Yes, so when I returned to music after years of not doing it, it felt familiar to me. It felt like home, with all of the emotional difficulties that came with it. I feel like I’m finally on the other side of it, and making this record definitely was a huge part of that healing process. But as I was really trying to build something, it felt very much like I was being constantly undermined by the voices in my own mind that came from, you know, my dad, ultimately – this kind of drumming it into me that I couldn’t do it, that it wasn’t my place to try and pursue music.

You close Another Life with a song called “Mother,” and I immediately recall John Lennon’s “Mother” that opens his confessional and cathartic Plastic Ono Band album, in which he expresses his feeling about his past, his parents, and rebuilding his life after the Beatles, which he saw then as this ultimately unhealthy escape route to his past.

It’s funny you say that about the Lennon song, because “Mother” was originally the opening song, but we changed the order. It’s the last song on the album now. I think it works there, to wrap it up, because it was the last song that I wrote.

You sing, “You didn’t deserve this / You didn’t deserve this.” Is this an expression of empathy for your mother?

Well, I think that when I was a kid, I oftentimes felt like my mom and my brother were my siblings, because we were all deferring to my dad. And so, yes, I felt close to her. But as I got older, we started having a lot of problems in our relationship. It’s better now and I have a good relationship with her, but there was a period where I really felt resentful of her because she wasn’t so much a parent, as a sibling.

Did she feel the same way as you did about your dad negatively controlling the family environment? Did you look at her as someone also being dismissed and did it lead to a bonding with her?

Not so much. I didn’t feel like she protected me from my dad. We worked through it. We really put a lot of effort into fixing our relationship and we even did a two-day intensive therapy thing together that she organized for us, so she really wanted to make our relationship better. And I did, too! I’m really happy that we did that because it was really hard for me for a few years feeling like I didn’t have any parents. I wasn’t close to my dad and then I was going through this difficult emotional situation with my mom. A lot of the songs on the record were written in the midst of that situation where I was really in the middle of some difficult emotional stuff. I was a mother, and I was trying to have a mother, to reconnect with her.

Can you relate to what she was going through, being a mom now? How old was she then?

When I was born, my mom was, I think, 29 or 30. My dad was 45. I’m 31 now. I had children in my twenties. When I was growing up, she was solely responsible for any kid related thing – picking us up from school, going to any events or whatever. She was the primary parent, even though my dad was in the house, he wasn’t involved in any kind of childrearing stuff.

You sing, “Oh, my beautiful mother / She isn’t meant to be treated this way.”

It’s interesting, because I initially wrote that song about the earth, but as I worked on it, and was going through all of this with my mother, it began to have a double meaning for sure. It came out as I was writing it. I had this feeling in my body the whole time that I was writing the album, where I wanted to express this feeling that I had, which was this deep sense of loss and sadness and helplessness and pain, which is something that I feel when I think about the earth and how it’s being treated. But, as I said, it became clear that those feelings were also connected to my mother. There’s a duality, I think, where it means both.

In “Acid Trip,” the opening song on the album, you sing about letting go. It’s the perfect opener since it encapsulates everything else on the record. Is that specifically about your childhood, your relationship with your dad? Or is it just about other things? What do the lines, “You are hard to leave behind, but it was time to go” refer to?

When I started writing that song, the feelings that I was having were centered around my dad, because after my parents got divorced, I tried really hard to maintain a relationship with him, but his mentality was kind of like he divorced all of us. He was moving on with his life in a different direction, and so, I tried to have a relationship with a person who had no interest in it. When I wrote that song, it was really a moment of… there was no getting around the fact that he closed a door, there’s nothing left there in which to build a relationship. But when I write songs, there is this cross-cross referencing that happens in my brain where I feel a feeling and then sometimes, I can apply it to other things that have happened in my life, that kind of branch off from the main kernel of the feeling. It’s very much like “Mother” at first being about the earth, but then it has very much to do with my mother. It became more literal in that sense. So, there are layers of references in my own process of writing. By the time I get to the end of a song, I feel like I’m writing about more things than my initial inspiration. In the end, “Acid Trip” wasn’t really about my dad or just my dad. It became about other relationships that I’ve left behind and other lives that were like other versions of myself. It started out as one thing and then it kind of expanded into having more layers by the end of it.

The last thing about that part of your past, which comes up a lot in these other songs; do you have any desire to send any of this music to your father, or you don’t care about that anymore?

No, I didn’t… and I don’t. I’ve only ever played him a few songs that I’ve written. And it was early on when I wrote my first EP. I played him the songs from that. That was like, 2015, I think. I was really hoping that we could bond over that and that it would be another way for us to connect, but it was clear even back then that that wasn’t going to happen, even through music. So, after that first time I didn’t share any music with him, mostly because he didn’t seem interested – and that was a really stressful experience for me to be wanting him to have more of a response than he had, you know?

I’m intrigued with “Bad Things.” Who is the person that “makes you want to do bad things”?

That song was inspired by a friend that I met, who completely altered my life at one point during all of this upheaval. I told you about her.

Yes, you’ve mentioned her to me before. Please tell the story.

There is this magazine I love called Sun Magazine. It’s the best. It’s this beautiful compendium of short stories, poems, and essays. It’s ad free and it’s in black and white. I read a story in it a few years ago and after I finished reading it, I remember saying, out loud, “Holy fuck!” It affected me so much. It was such a beautiful story. I had never done this before, but I needed to talk to the author, so I found her on Twitter or Instagram and we became really good friends. We started this month-long conversation that just kept going and going. To be honest, it kind of felt like we were falling in love. We’d developed such a strong connection.

Then she came to visit me from California. She came here and stayed for ten days, and you know, I’m married. I have two kids. I’ve built a life that’s grounded in a lot of ways, which is a good thing for me to feel that security, because it’s something that I never experienced growing up. But at the same time, this relationship that I had with this friend just felt so… free. It felt like we could just run off together, and start a life, living for our art, doing whatever we wanted. It just felt like anything was possible. Creatively, I think we really inspired each other, because we talked a lot about ideas for things that we wanted to do, and so, in that way, it was also very creatively stimulating.

Considering that at the same time I loved my life – my husband, my children, my home – she definitely made me want to do bad things, like fly away. This created a dissonance, where reality butted up against fantasy, and I had to come to the realization that that’s not real life.

But it does reveal a part of you that was dormant.

Yeah, for sure. It also ties in, I think, with the theme of a lot of the songs on the album, finding another life – wanting to escape or wanting to live a different life, which

is not always the best.

“Little Love” is very much like that. It is a damaging relationship song that you’re working through by telling its story.

That was about an intense relationship that I had when I was in college. I was 20 at the time and while we were breaking up, I got pregnant and had an abortion. It was the ending of so many things at once – the ending of this fantasy love, a child, so many possibilities that I had imagined for us. The song is basically about the arc of that and the emotions that came with leaving it all behind at such a young age.

This is why I see much of what is in this record reflecting your novella. It works as catharsis, but also as a personal history for another person that you used to be. Maybe all of it is in this time capsule that you had to let go of in “Acid Trip” and also this hazy recollection, “Did this even happened to me?” Like… Another Life.

Yes. Exactly.

All of these songs have these Dickensian “Best of times/Worst of times” opening lines that really take you into the song – “It’s hurting me to feel this way /

My heart wants to go on strike,” (“Another Life”), “Always thought I wasn’t good enough / Cause nothing’s good enough for you,” (“Acid Trip”) and “Why am I so undecided / I’m always of two different minds”, (“Bad Things”) “I haven’t felt this bad in a long time / Nothing numbs the pain,” (“Bloodline”). Coming to these songs as a writer, there’s just no parsing these lyrics. They’re right in your face. No artifice or metaphor… very little, anyway.

Yeah, that’s because I didn’t write any songs that I didn’t know what they were about. Every song that I wrote came from basically feeling something and distilling it into a sentence, which was the first line in every case, and then meditating on that sentence that kind of had the whole song inside of it. Then, unraveling it from there.

From “Bloodline”: “I tried to be happy, but I’m not fine / Something’s there in my bloodline” is something I think we all feel.

It’s what I was also trying to say in “Neon Sign.” Like I said, a few years ago, I was really grappling with a lot of things and also at the same time holding them very much inside. That song came about because I had this fight with Shawn, I really got mad, and started yelling like I had never done before. Afterwards, I felt afraid of myself, the way I was afraid of my father. I wondered, “Am I turning into my dad? Am I going damage him the way my dad damaged my mom?” And the idea is, “Do I have this terrible, bright, unavoidable thing inside of me that is maybe not visible from the outside, but is clearly there for me to see, and maybe for other people to find once I peel back the layers of who I am?” What I was going through, and being more honest about it with myself, I kind of stopped feeling so much like I had this scary thing inside of me. But during that time, it was a big concern for me, like wondering what this was that I had.

This one incident brought this out?

Yeah, I mean, it wasn’t just one incident. I was going through a really hard time, and it translated into difficulties in my relationship with Shawn just because there’s so much I was dealing with that I didn’t have the wherewithal to be a good partner.

Right. Just like your father didn’t have the wherewithal to be a good father, so now you’re back to that again.

Exactly. I was trying really hard to keep it together and do the right thing – to keep my temper under control and not be triggered by things. I just wasn’t really holding it together that well. I think I had gone quite a while without freaking out about something and then I felt really bad when I did. “Neon Sign” is about being afraid of what I’m carrying inside of me.

Is that what you are saying in “Unkind”? That is one of my favorite melodies on the record and your singing is exquisite. Do you see yourself as unkind?

Thank you. I’d say, it’s a theme in my life – that I fantasize about other lives. And sometimes I just fall in love with a stranger, or with the idea of a stranger. For instance, I’ll meet someone one time and then imagine what it would be like if we lived together and had a different life. It’s not something that happens to me as much now, but when I was really struggling emotionally, I was escaping my real life by living these other lives inside of my head. That song is me having a conversation with the fantasy and saying, “Leave me alone! You’re lying to me, and I don’t believe you!”

I think it’s important for a writer to live mentally on a razor’s edge and that’s why we get accused of exaggerating events or embellishing stories to make them stick more in the reader’s mind, or in this case, the listener’s mind. It’s probably healthy to not constantly edit your own thoughts or fantasies. Repression is not healthy for writers.

Yes, I learned that you can’t push it down and try to silence it, because it doesn’t go away. For me, music and writing songs is a very healthy and therefore a necessary outlet for me to express all of that. When I say “express,” I mean “talk about,” but I also mean drain the pressure that can build up if you silence it all.

I’m reminded of that healthy outlet when you sing, “I’m fucked up in the head.” If you are expressing this then you’re not insane. People who are insane don’t think they’re insane.

Yeah, totally.

This brings me to “Vampire” – this idea that something is feeding off something else, stealing it, which can happen to us in any walk of life. I don’t know where you were going with that. That’s how I read that song.

Yeah, honestly, that one was me trying to get some control over my feelings. My dad was harassing me. When my parents were going through their divorce, I was very much put in the middle of it. He wasn’t allowed to talk to my mom because she had a restraining order. And so, he was trying to pressure me to be like a proxy. It was just so emotionally overwhelming and draining and none of my boundaries were being respected. It was just constant, emotional chaos. I was in this reading jag, and during it I read Dracula and Frankenstein, and it just really felt similar to me. The idea of a vampire that’s sucking someone’s blood. Like a person that’s sucking someone’s lifeblood away and you can’t pin them down and get them to stop. They’re completely supernatural, somehow.

What’s that great line in Frankenstein? “I have love in me the likes of which you can scarcely imagine and rage the likes of which you would not believe. If I cannot satisfy the one, I will indulge the other.” Once again, the extreme level of conditional love. What about “Vikodin,” another favorite track of mine. Like “Vampire,” I see this less literally about a drug than something else.

That was one of the songs taking an older feeling and pulling it up from the depths.

It was another college experience during that intense relationship that was going on that I told you about earlier. The one I wrote about in “Little Love.” I was looking for a way out of that relationship because it was so consuming and suffocating in a way. I became really infatuated with this other person and my feelings for him were so intense that it really felt like a drug. It felt like my infatuation with this other person was a way for me to numb the pain that I was feeling from the dissolution of this other relationship.

I don’t mean to belittle it, but I guess you would call it a rebound type thing where you find someone completely opposite of the person you’re with and that’s the person that you need to be with. The whole time you’re second-guessing yourself if you do that. It’s an easier pain to swallow sometimes when you’re helpless in it.

At this point in the conversation McLean’s daughters barge in and begin enthusiastically hugging her. It is a very joyous and sweet moment. A smile crosses her face, as she tries to corral them. Her husband, Shawn comes in and says hello before ushering them out. Before long Maya comes back in. We have a little chat and I am inspired to ask Jackie if she sees in her daughters the final chapter in this battle to erase her past, find meaning and closure – her parents, pasts loves, mental and emotional struggles, and the music of Another Life, that reveals much of it.

“I definitely see pieces of myself in my daughters, for sure,” she says, still smiling. “They’re just their own little beings in so many ways. I’m just lucky to have them and I don’t want to hurt them in any way. All I want to do is to protect them and help them to be who they are, not what I want them to be. I’m a little bit wary, I guess, of looking for myself too much in them, because I want them to really feel like they can be their own people.”

Jackie McLean / Roan Yellowthorn’s Another Life is out now for your musical and inspirational pleasures!